The vibrant spirit of protest culture has seldom seemed more alive than it does today. But the legacy of that spirit, its place in historical and living memory, is a delicate and fragile thing. Its strident passion and creativity easily fade with the echo of appeals to social conscience that do not sit well with those they challenge—institutions and interests that are often actively bent on burying them in the silence of a forgotten past. Take the example of Frigidaire, an irreverent and boldly satirical magazine with roots in movements fighting for diversity and against repression that swept across Italy in the 1970s. For 50 years, Frigidaire and its editor Vincenzo Sparagna have kept that spirit of youthful rebellion alive, serving up a feisty blend of subversive comics, performance art, stunts, activism, and political and cultural reportage that has shaped critical minds of young Italians for generations. A reservoir of creative revolt, its archives failed to find a home in the cultural institutions of Italy, where the turbulence of the 1970s still seems far too close for comfort. Like many other troublesome reminders of the not-so-distant past, Frigidaire’s archives are now housed at Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, where they form part of Yale’s growing collections of the postwar culture of protest in Europe. In Italy, however, the legacy of Frigidaire is now under attack from radical right-wing extremists who are trying to eradicate the magazine’s museum and editorial headquarters in Umbria. Never has this living link to Italy’s rebellious past been in greater peril.

Founded in 1980, Frigidaire emerged from the ashes of youthful revolt that culminated in the Movimento del ’77, a broad and shifting alliance of movements that fought against repression in ways that significantly broadened conceptions of class struggle that had traditionally formed the rallying call of the orthodox left. Feminists, activists for gay and lesbian rights, transsexual identities, protests against police brutality and the criminalization of “deviant” behavior, prison riots, campaigns against war, militarism, nuclear power, a budding environmentalist movement and many other actors besides spontaneously joined in the common cause of fighting for civil rights, diversity, and freedom from oppression. Sustaining this rebellious new sense of shared identity were hundreds of self-produced underground and counterculture magazines, which thrived as “the Movement” spread in the 1970s. Some protesters took a more aggressive stance, however, and the tension between creativity and violence as means of resistance played out in escalating clashes with authorities and acts of militant extremism that eventually spelled the end of the Movement ‘77. With the abduction and assassination of former prime minister Aldo Moro in 1978, the complexity and diversity of the broad-based rebellion collapsed under calls for law and order and a hail of repressive legislation enacted not only in Italy but across Europe at the end of the 1970s. A few years later this vibrant protest culture already seemed to belong to a forgotten past, its memory replaced by conformity to the demands of a new political reality marked by the deep trauma of “the years of lead.”

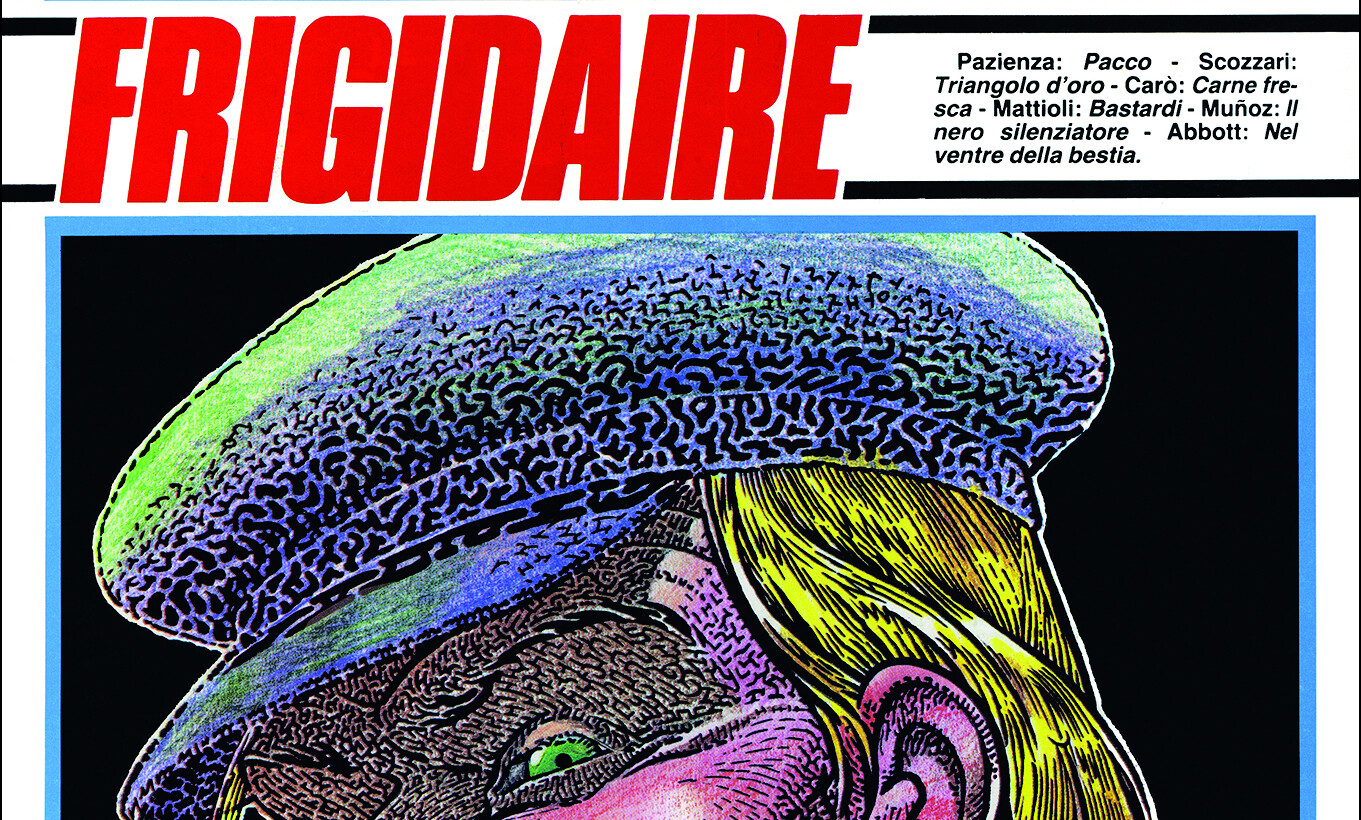

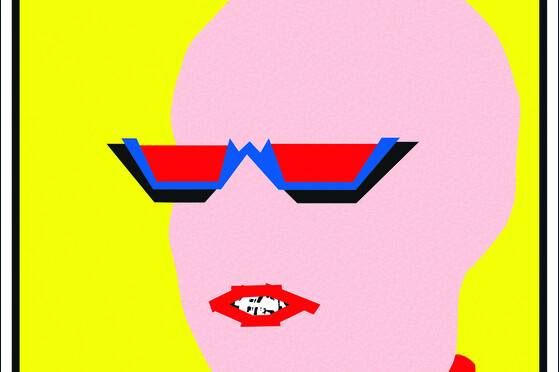

Among the Movement’s few survivors were fumetti artists, masters of a form of satirical comics that had come into its own with the thriving ‘zine culture of the 1970s. Joining this group in the subversive review Il Male (“Evil”), Sparagna went on to found Frigidaire at the beginning of the new decade, its title being a reflection of the magazine’s goal of serving up countercultural fare to readers “cold,” that is dispassionately, appropriate to the chilly political climate of Italy in the 1980s. Sandwiched between colorful, irreverent, beautifully produced comics by masters of the art like Andrea Pazienza, Mario Schifano, Filippo Scozzari, and Stefano Tamburini, virtually all of the causes of the vanished Movement reappeared in articles on art, culture, and political reportage: gay, lesbian, trans identities, sexual liberation; prison rights; solidarity with struggles in Africa and reports on developments there. Sparagna published letters from former activists languishing in Italy’s prisons, and the first coverage of the AIDS crisis in Europe also appeared in Frigidaire, which patiently explained to readers that it was not a “gay cancer.” The magazine’s commitment to drawing attention to such causes was not limited to editorials. After the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the editorial staff went to the occupied country, taking along a fake issue of The Red Star (the Red Army’s version of Stars and Stripes) with the headline in Russian: “Enough War! Everyone Go Home!” Posting it in public places and photographing the response of passers-by, Sparagna and his colleagues met in person with the perplexed Mujahideen (who seemed baffled by the use of humor as a weapon) before going on to do the same in Russia and throughout Eastern Europe. In the 1990s, Frigidaire showed similar courage in documenting the violence that erupted with the fight to end the power of the Mafia in Southern Italy. These are just a few examples of the magazine’s continuing engagement with issues of social justice and the fight against oppression. Many more are waiting to be discovered in the Frigidaire archives at Beinecke.

Over time Frigidaire became a household word for generations of Italians, analogous perhaps to the National Lampoon or Saturday Night Live in America in those years. While the lawsuits piled up, Sparagna published other spin-offs such as what appeared to be a pirate edition of the Roman newspaper La Repubblica and Il Vomito (just like it sounds), which was devoted entirely to publishing the“sub-literary” responses of readers to Frigidaire and what it stood for. Sparagna also took the time to mentor another generation of young fumetti artists who have now taken up their role and are pursuing their own agendas in the new millennium. In 2005 Sparagna moved the magazine’s editorial headquarters from Rome to a small and remote rural estate leased from the nearby town of Giano in the mountains of Umbria. Dubbed the “Republic of Frigolandia Frigidaire’s new home includes simple guest quarters, a recreation area, an amphitheater, and a museum displaying issues of Sparagna’s various magazine ventures, posters, ephemera, and the “never-before-seen-art” of Frigidaire’s fumetti artists (the magazine’s archives, which had previously been housed here as well, are now at Yale). According to Article I of its “Constitution,” “The Republic of Frigolandia is a free union of men, women, children, animals, plants, and minerals founded on imagination. The constitutive principles of the Republic are: peaceful coexistence and human solidarity; respect for the Earth and all living beings; rejection of all types of intolerance, whether cultural, social, ethnic, or religious.” For a modest fee, like-minded people can purchase “passports” that entitle them to stay on the grounds and enjoy the Republic’s hospitality for up to a week every year.

But now, in the midst of the crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic in Italy, Frigidaire and Sparagna’s Republic of Frigolandia are under attack. Under pressure from the Umbria branch of right-wing extremist Northern League, the city council of Giano dell’Umbria is attempting to evict Sparagna in violation of a contract that has been honored since 2005, effectively closing down the museum and eradicating the last surviving memory of a suppressed movement for social justice and cultural diversity that continues to face institutional neglect if not outright hostility. “After too many years of misgovernment by the left and bankrupt and self-referential management of public affairs,” the League and its allies are “called upon for strong actions of renewal and rupture with the past,” the opponents of Frigolandia proclaim. “Even though I’m almost 74 years old, I still have to defend myself from the umpteenth persecution by an obtuse and nefarious political class tainted by a creeping odious fascism,” Sparagna recently wrote the curator of his archives at Beinecke in a personal appeal for help. “I cannot even imagine what a disaster it would be to dismantle Frigolandia and move who knows where with the 4000 plates, drawings, paintings, sculptures etc. we have hosted here, plus all the rest you know about …”

Those wanting to support Frigidaire and the legacy of protest culture in Italy since the 70s can sign the petition at Change.org.