“Art for the Wrong Reason” By Emily Kopley

this essay originally appeared in The New Journal in December 2004

Admirers of Mark Twain’s literature might be unaware of the humorist’s hidden talent for doodling on dinner napkins while blindfolded. Proof of Twain’s prowess lies in the basement archive of the Beinecke, which houses, in addition to the manuscript of A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, “Un-Eyed Dog,” a sketch “Executed instantaneously and blindfolded by / Truly Yours/ Mark Twain/ (Educated artist).” The same jaunty humor of Twain’s caption colors the title of the collection to which this sketch belongs, the “Art for the Wrong Reason” cache of the Yale Collection of American Literature (YCAL). The collection is so named because its 68 works were amassed primarily out of interest in the writers who made them and less out of appreciation for the work’s artistic merit. These works range from the hastily-composed caricature to the ambitious lithograph or oil painting. Interest in the writers behind the works lay with Norman Holmes Pearson (BA 1932, Ph. D. 1941), Yale Professor of English and American studies as well as advisor to YCAL. Upon his death in 1975, Pearson donated all his personal and scholarly papers to the Beinecke, as well as what he had himself dubbed the “Art for the Wrong Reason” collection. The scholar’s own story informs this collection.

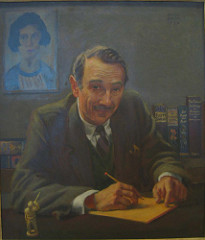

A portrait of Pearson graces a wall just outside reading room in the Beinecke and reveals not only his warm, intelligently wrinkled countenance, but also his many activities. Set in the professor’s HGS study, the painting boasts in its background the Oxford Anthology of American Literature, which Pearson edited with his friend William Rose Benet. Next to the anthology is Dusty Diamonds, a “boys’ book” representing the genre of which Pearson collected fine editions. Bust most striking is the painting of a woman whose cold face contrasts markedly with Pearson’s own: it is the face of “Arabella,” who stares out of D. H. Lawrence’s only portrait, reproduced in the portrait of Pearson. Arabella’s distant, overly large eyes and awkwardly open mouth suggest that Lawrence was wise to stick to his day job. Pearson displayed the portrait in his office apparently because his wife declared there to be “too much artistically wrong” with it to be displayed in the Pearson home. Pearson acquired “Arabella” for his collection from the model who sat for it. Much of the rest of the art in Pearson’s collection was given to him by writer-friends, who included e. e. cummings, William Carlos Williams, Tom Wolfe, and Denise Levertov. One such piece is by Pearson’s fellow anthologist, Benet: a colorful drawing titled “Whale Gallant” that anticipates Dr. Seuss. Purchased pieces by Robert Louis Stevenson, Thackeray, Proust, and Hugo, among others, round out the group.

Pearson’s interest in writers’ art stemmed from his desire to gain a fuller picture (so to speak) of the writers whose literature he enjoyed. Pearson wrote, “[I] like to meditate on the relationship between a writer’s painting and his poetry and prose. Is there a correlation? Does a writer write better because of learning to hold a bush?” One might look to e. e. cummings’ paintings for an answer. Cummings and Hermann Hesse are the two writers in the collection who artistic endeavors are particularly extensive and well-known. Cummings’ watercolor View of Silver Lake is intensely colorful and joyous, yet deliberate. This controlled euphoria is familiar to the reader of such poetry as “Picasso / you give us things / which / bulge:grunting lungs pumped full of sharp thick mind.” Although Cummings’ graceful paintings do not themselves “bulge” with “grunting lungs,” they demonstrate the poet’s serious aspiration to be a gentler Picasso.

Less well-known is the art of William Carlos Williams, who studied painting before he came to write poetry. The calm, bucolic mood of his green-and-brown New Jersey landscape, View of Passaic River, shadows the less calm America of his long poem Paterson. Says Nancy Kuhl, Associate Curator of YCAL and occupant of the office in which this paintings hangs, “So few people seem to know that Williams painted at all—even those who otherwise know a great deal about his work and his life. When I mention the painting in my office (or show it off) I think people take it in as a painting, but they begin also to factor the fact of it into their larger understanding of the poet/man/doctor/artist who painted it.” Seeing the art of other writers besides Williams and cummings likewise enhances familiarity with the people behind the pen.Like Williams, Gunter Grass also began as a visual artist. His lithograph of four huddling, cloaked men whose heads each resemble that of The Scream haunts the collection. So does Tom Wolfe’s ink sketch of Hugh Hefner as a smoking, boozing, dictatorial imp. Less threatening but no less impish is Henry Miller’s watercolor self-portrait in which abstract blobs almost accidentally fuse to compose a blank-eyed bohemian. George Bernard Shaw’s own watercolor self-portrait, as an ethereal Don Quixote, reveals the playwright’s romantic and wry side. Some art in the collection is more strange than illuminating. Hilaire Belloc, a French-turned-British writer of poetry, literary criticism, and military and social history, contributes an ink sketch of cartoonish goblins and fairies surrounding a watercolor inset of a nebulous landscape. By way of clarification, a Latin inscription captions the picture. Queen Victoria’s miniature figure studies, the product of her fourteen-year-old hand, also honor the archive. The Queen renders a pair of horses, a horse-riding Turk, and a gypsy girl with a goat and tambourine in simple lines and dutiful cross-hatching.

The “Art for the Wrong Reason” collection was featured in a Beinecke exhibit about twenty years ago. Since then, most of the art, which is flat and unframed, has lain in the archive in two grey, acid-free boxes, to emerge periodically at the request of scholars eager to know: Would a Twain sketch by any other name look as sweet? Perhaps not, but a Williams painting or Grass lithograph might. These works of art, though not masterpieces, help to piece together the personalities of masters. And in aiming for a deeper understanding of great writers, as Pearson did, there abounds right reason. Records for works in the “Art for the Wrong Reason” collection and other art works in the Yale Collection of American Literature can be located by searching the Beinecke Library’s Art Storage database; images of some pieces in the collection can be viewed in the Beinecke Digital Library. Related archival materials can be located in the Beinecke Library’s Finding Aid Database. Books by the collector and artists can be located in Orbis, Yale Library’s catalog for books. Images: Norman Holmes Pearson by Deane Keller; Arabella by D.H. Lawrence; Untitled Landscape by E. E. Cummings; Passaic River by William Carlos Williams; Still Life By Denton Welch. Special thanks to Emily Kopley and The New Journal for permission to reprint this essay.