The swift downfall of Queen Anne Boleyn in May 1536 (see: “From my doleful prison in the Tower”) is talked about perhaps as much today as it was when the scandalous events unfolded during the unquiet reign of King Henry VIII. Some historians pin Anne Boleyn’s demise squarely on the shoulders of Thomas Cromwell, the King’s chief councilor and Lord Privy Seal.

Perhaps less conspicuous, and certainly less lamented, is the equally swift downfall of Cromwell himself shortly thereafter. Whatever may be the truth, Hilary Mantel’s “Wolf Hall” series and an excellent biography by John Schofield (The Rise & Fall of Thomas Cromwell; The History Press, 2008) turn attention on the previously unconsidered interior life of Cromwell. These works lend him sympathy in modern readers’ eyes and dispel some of the myths of Cromwell’s unflattering legacy.

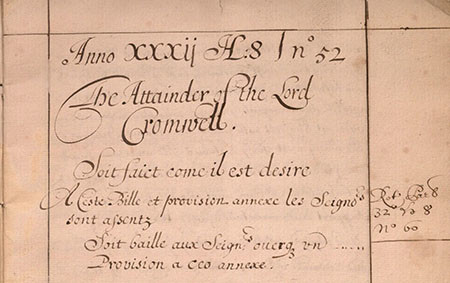

The Beinecke holds a seventeenth-century manuscript copy of the attainder – Cromwell’s death warrant – fifteen pages long, written in a tidy secretary hand. Among the litany of damning charges, Cromwell is described as being a man of “very base and low degree,” whom the King raised to “the State of an Earle,” and whom, through the King’s singular favor, received “manifold gifts aswell of goods and of lands and offices.” The said Cromwell then disregarded his Majestie’s “singular trust and confidence” to become “the most false & corrupt Traytour, Deceivour & circumventor” against King Henry’s “most Royall person and Imperiall Crown.”

Cromwell is charged with usurping the King’s authority; giving safe passage to traitors and heretics; misappropriating funds; taking bribes; circulating false books, possessing false doctrinal opinions, and, in short, being a treasonous and heretical person who conducted himself in a way “which is detestable and to be abhorred amongst all good Subjects in any Christian Realme.”

Anne of Cleves is never mentioned in the lengthy indictment, though legend has long held that her unhappy union with Henry VIII was the cause of Cromwell’s undoing.

There was no trial, and Cromwell was executed on July 28, 1540, on Tower Hill. Edward Hall’s account described the headsman as “a ragged and Boocherly miser, whiche very ungoodly perfourmed the office.” Cromwell’s beheading took place a scant four years after Anne Boleyn became England’s first la reine sans tete.

It was only a matter of months before Henry VIII began to regret Cromwell’s execution. The French ambassador Charles de Marillac reported the King blaming some of his closest councilors for bringing about false accusations in the attainder and thereby requiring the King “put to death the most faithful servant he ever had.”