By Dante Haughton

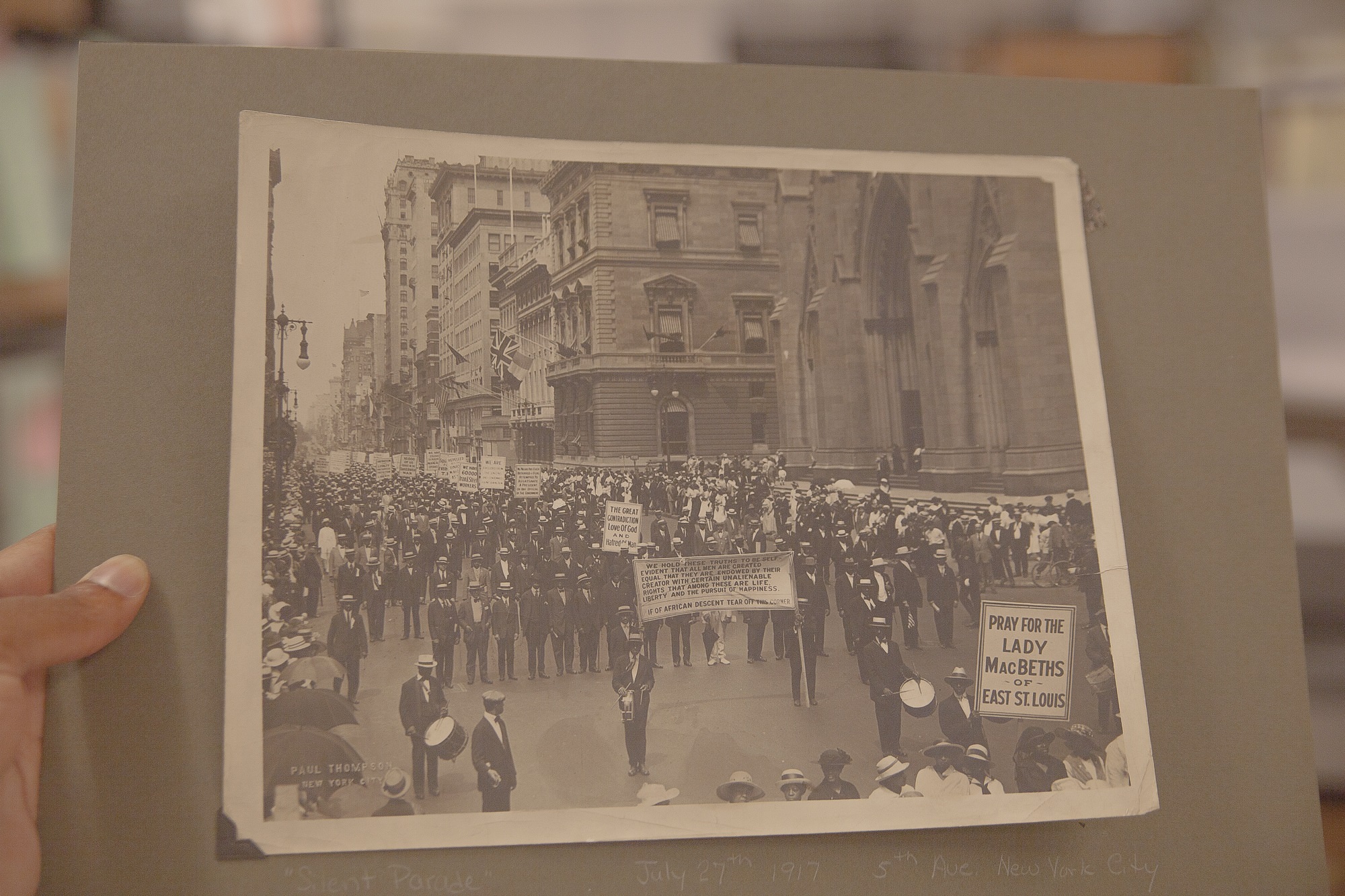

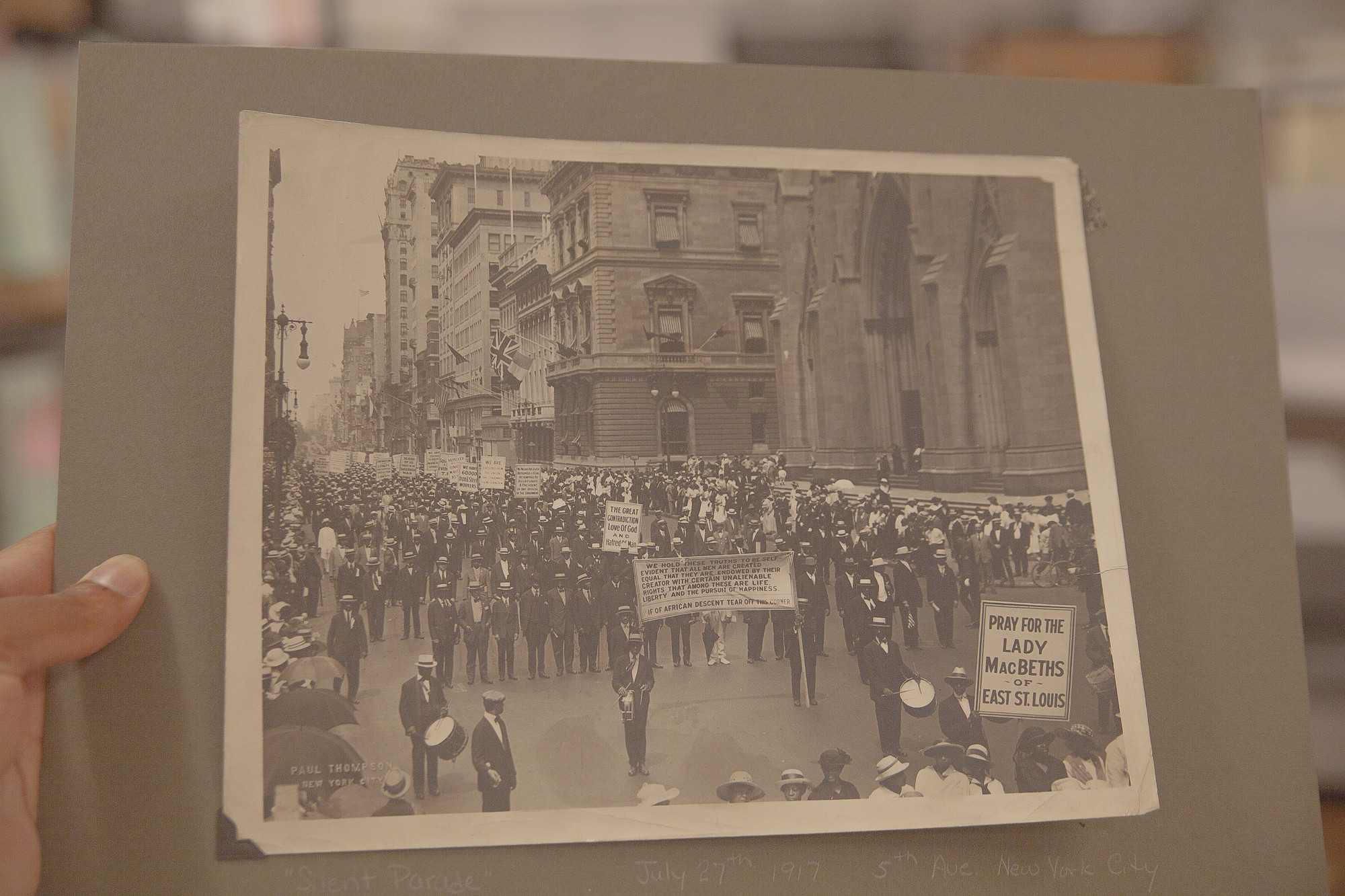

On July 28, 1917, near the site where Trump Tower now sits, at Fifth Avenue and 57th Street, 10,000 plus men, women and children marched in strong, silent formation. Not a word echoed through the canyon of New York streets. In their banners, the activists bore witness and carried a protest in the heat of a hostile summer. The Negro Silent Protest Parade addressed the government’s indifference to ongoing violence acted upon African American citizens by white Americans from the country’s origins. The 1917 march, an early act of nonviolent civil action, was orchestrated by James Weldon Johnson, a field secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), in response to the race riots, such as the East St. Louis Massacre, that occurred earlier that year. Because the perpetrators of these hateful event went untried, the NAACP called for federal action.

Because of World War I, jobs in factories that produce metals had become vacant while the demand for their products rose. Many African American families moved from the south to northern cities hoping to settle more securely in places like East St. Louis, Illinois, where factory owners took advantage of “The Great Migration” by recruiting non-unionized black men to satisfy the growing demand of labor. Many white residents complained the new hiring was “unfair competition.”

On July 1, 1917, following a protest to the mayor in May in which African Americans were assaulted, a car of white men drove through a predominantly black neighborhood shooting into houses and other establishments. Later that day, a group of men organized in defense of their neighborhood, shooting at a similar looking car driving through, killing two detectives sent to investigate the earlier incident. White residents of the town, after seeing the car, formed a mob and raided African American neighborhoods, from July 2 through the night of July 3, murdering black residents and burning black residences. The National Guard, like the local police force, focused on mitigating resistance, instead of stopping the violence. Ultimately, between 50 and 200 men, women, and children are drowned, beaten, lynched, or burned “for seeking to earn an honest living”, as the march organizers wrote, while 6,000 of the survivors flee their homes to escape violence and arson.

Addressing this hateful ambush, the NAACP began recruiting black people for its nonviolent response to evil. On July 28, wearing all white to represent innocence, children led a unit of women in white followed by men wearing black in the peaceful protest. Their banners examined American hypocrisies, recalling “the first blood for American independence”, which was “shed by a Negro”, as one of many contributions black people have made for the union without reciprocity. In the following week, Johnson and other black leaders petitioned President Wilson and Congress that lynching be made a federal crime to hold white offenders accountable for murder and prevent further loss of innocent life. They were turned away without regard, but their action sowed seeds that would grow in subsequent decades.

In 1917, long before the internet or text messaging, people of all ages emoted in New York to respond to an event in Illinois, and acts of violence across the country, to deliver a message to the White House and leaders in Washington. The photographs and documents the Beinecke Library holds, including the the original petition, give us documentary material to remember this historical event that set the precedent for later nonviolent marches for civil rights. It shows us today, in a time when the country’s division is still pronounced vividly, the power of unity and mobilization.

Bibliography

Newman, Alex. “NAACP Silent Protest Parade, New York City (1917).” Blackpast.Org, 2017, http://www.blackpast.org/aah/naacp-silent-protest-parade-new-york-city-1917.

“NAACP Silent Protest Parade, Flyer & Memo, July 1917.” Nationalhumanitiescenter.Org, 2014, https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/maai2/forward/text4/silentprotest.pdf

“Ten Thousand African Americans March In New York City To Protest Racial Violence.” Blackmedamine.Blogspot.Com, 2015, http://blackmediamine.blogspot.com/2015/07/silent-protest-parade-july-28-1917.html?spref=tw&m=1.

Buescher, John. “East St. Louis Massacre.” Teachinghistory.Org, http://teachinghistory.org/history-content/ask-a-historian/24297.

Johnson, James, John Nail, and Frederick Asbury Cullen. Petition Re Lynching. 2017. Letter. James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection, Yale Collection of Literature. New Haven, CT.