Remarks by Melissa Barton, Curator of Drama & Prose, Yale Collection of American Literature, at the opening of Destined to Be Known: The James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection at 75, an exhibition on view at Beinecke Library through December 10, 2016

It is my great privilege to be able to tell you a little bit about James Weldon Johnson and the collection created in his memory.

One of the architects of the Harlem Renaissance, James Weldon Johnson was himself a true renaissance man. A man of letters and of the law, author of solemn lyrics and popular love songs, Johnson led a multi-faceted life and his career was one of constant reinvention. Living through dark and tumultuous years in the history of African American civil rights, Johnson can be found in many of the significant moments of that history. He worked as a “chair boy” wheeling visitors around the vast fair grounds at the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, before going on to a career that included education, law, popular music, public service, political advocacy, and authorship.

As a field secretary the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Johnson opened NAACP offices throughout the United States, work that was challenging and dangerous. Appointed the first African American executive secretary of the NAACP, Johnson became the nation’s most outspoken critic of the practice of lynching. As a member of the songwriting trio Cole and Johnson Brothers, Johnson participated in the revolution of ragtime music. As a man of letters, he supported, advocated, and contributed to one of the most extraordinary literary moments in history. As an editor and writer, he produced two anthologies of poetry and two anthologies of spirituals—the first of their kind—as well as three volumes of his own poetry, a novel, an autobiography, a history of African Americans in New York, and countless essays. As a member of the United States consular service stationed in Latin America, Johnson witnessed American imperialism in action.

When Johnson was killed in a car accident in 1938, just weeks after his 67th birthday, there was tremendous demand for a memorial to his memory. Though plans were made for a statue in Manhattan, the memorial committee, under the leadership of Johnson’s friend, author, collector, patron, and photographer Carl Van Vechten, decided instead to found a collection of African American Arts and Letters at Yale in his honor.

Van Vechten formally founded the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of African American Arts and Letters in 1941, when he pledged to donate his large library of African American books to the Yale Library. To this, Van Vechten would add his correspondence with numerous prominent figures in African American literature, music, art, theatre, and politics, as well as thousands of portrait photographs of nearly everyone who was anyone in the arts—black or white—between 1932 and his death in 1964. With the help of Dorothy Peterson and Harold Jackman, Van Vechten began to solicit donations from others as well. Soon after the collection’s founding, Johnson’s widow Grace Nail Johnson added her husband’s personal papers, which were followed by those of Walter White and Poppy Cannon White, Langston Hughes, Chester Himes, and Dorothy Peterson, as well as Johnson’s vast personal library. By the time the collection formally opened to the public in 1950, Van Vechten’s typed list cataloging the collection ran to over 650 pages, and the list of donors numbered in the hundreds.

Yale and Beinecke continued to develop the collection, adding the papers of Richard Wright, Jean Toomer, theatre director Lloyd Richards, the records of the poetry collective Cave Canem, the papers of its founders Toi Derricotte and Cornelius Eady, and the papers of Yusef Komunyakaa. Expanding our holdings in the 19th century, we added the enormous Randolph Linsly Simpson Collection of photographs of African Americans, as well as important manuscripts like the Bondwoman’s Narrative by Hannah Crafts/Hannah Bond and The Life and Adventures of a Haunted Convict by Austin Reed. Now, 75 years after its founding, the James Weldon Johnson collection spans the entire history of African American letters, from Phillis Wheatley to the present day, and nearly every genre of written material, from city directories and travel guides to sheet music and film pressbooks, from photograph albums to manuscripts to email. It is a large and heterogeneous collection that attempts, more and more, to document the entire history of African American print culture. It is also the most consulted collection in the Beinecke Library’s holdings.

When Carl Van Vechten founded the collection, he published articles in the African American journals Crisis and Opportunity promoting the collection, soliciting donations, and explaining how fitting such a collection would be to honoring what he called Johnson’s lifelong commitment to “cultural development as a means of advancing the dignity of the American Negro in national life.”[1] Van Vechten referred to Johnson’s own words from his 1922 preface to the Book of American Negro Poetry:

A people may become great through many means, but there is only one measure by which its greatness is recognized and acknowledged. The final measure of the greatness of all peoples is the amount and standard of the literature and art they have produced. The world does not know that a people is great until that people produces great literature and art. No people that has produced great literature and art has ever been looked upon by the world as distinctly inferior.[2]

Johnson here articulates what has become a common shorthand for describing the cultural production of African Americans in the Jim Crow period: the cultural production of African Americans would contribute to the fight for equality where other means of political action had become circumscribed. For Van Vechten, a collection at a major university library—the first of its kind—would provide the recognition and the acknowledgement that Johnson calls for. But the collection has also become the foundation of decades of scholarship in African American Studies. It has inspired more than half a century’s worth of students to engage with this history, which President Obama said earlier this week, echoing James Weldon Johnson’s own words, is an essential part of our American history, and I would venture to add it is an essential part of the history of modernity. It inspired me, a sophomore in Robert Stepto’s African American literature survey, when he showed us—and this will date me a bit—one of his treasured slide reproductions of Miguel Covarrubias’s jacket for Langston Hughes’s first book, The Weary Blues. And I imagine that the materials in this collection have had an impact on many of you.

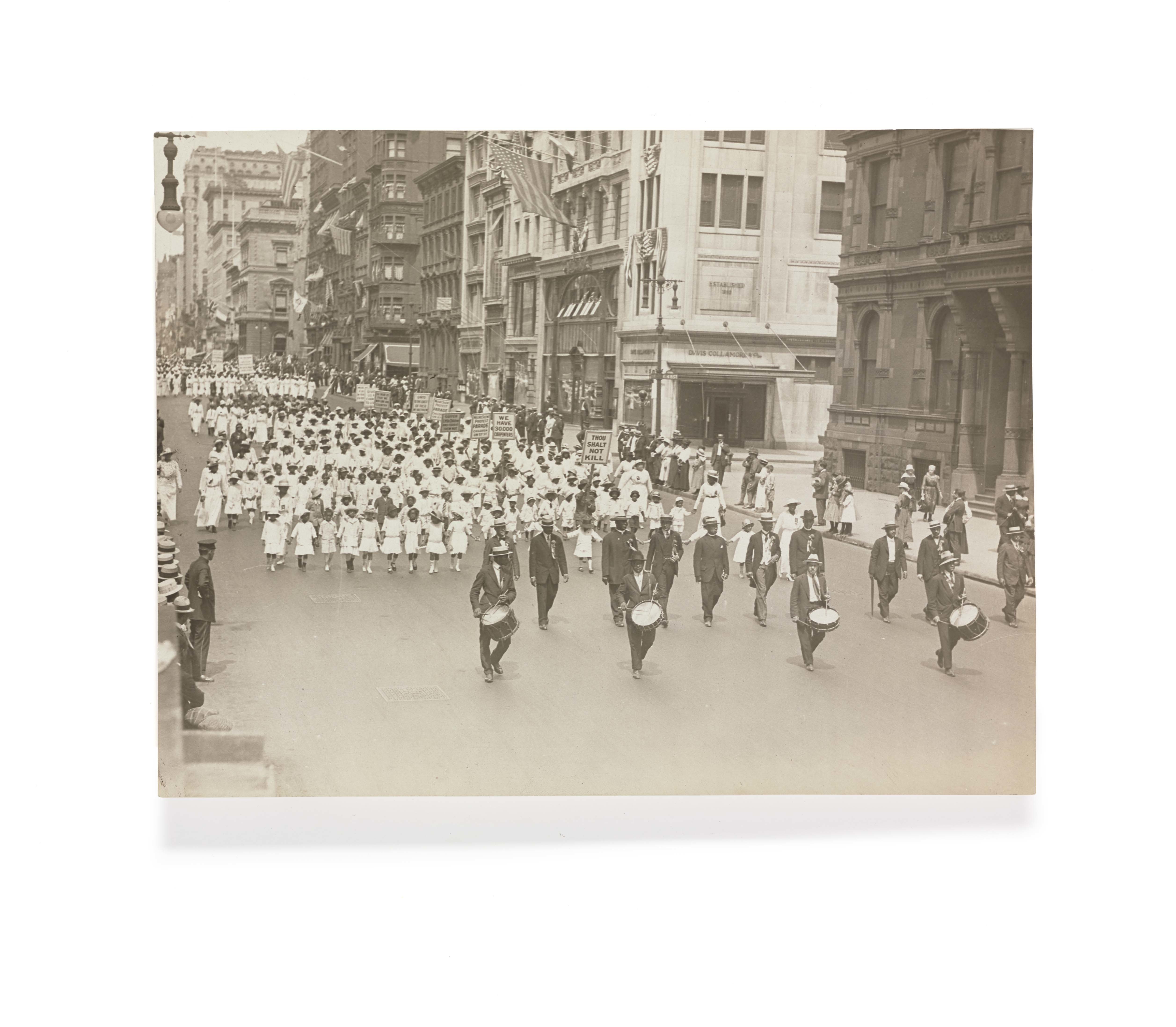

I just wanted to share one other example: several weeks ago as I was preparing this spring’s Harlem Renaissance exhibition, I was looking at photographs of the 1917 Negro Silent Protest Parade. This was a mass demonstration organized by the NAACP as a response to violent attacks on African Americans in East St. Louis, Illinois; ten thousand people marched two miles down Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, from Central Park to Madison Square, in silence, accompanied only by the sound of drums. No photograph could entirely capture the sight of thousands of African American women and children, dressed in white, walking in silence down the middle of the street, carrying signs that read “Thou Shalt Not Kill.” But still, even though I’d seen these photographs many times before, I was suddenly struck, quite profoundly, by the resonance between that moment and our present moment. I felt the distance of 99 years between me and that photograph collapse. As a historian of literature and culture I tend to resist easy comparisons between our past and present, so I was all the more taken aback by my sudden definite feeling of resonance. I won’t venture to say anything especially profound about the relationship between that moment and this one. I will only say that I know that we can’t begin to examine that relationship without collections like the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection.

The Silent Protest Parade was undoubtedly a political act, but it was also a beautiful one, carried out at a time when the tension between the beautiful and the political in African American art was a subject of constant discussion and debate. This is another way that James Weldon Johnson, a key planner of that event, exemplified in his own work grappling with that tension, not choosing one side, but embracing many sides, and many approaches. In the same way, the heterogeneity of the collection suits the man whose name it bears. So, this afternoon we celebrate that collection by celebrating the life and work of James Weldon Johnson. We choose to focus on the many great works of art he created. In so doing, we celebrate the power of literature that he recognized—not just to bring dignity and humanity to people suffering from a racist state, but also to give people space to claim beauty, to enjoy art the way Johnson, a man of wide-ranging tastes, loved Florence Mills and folk sermons, or the way the Ex-Colored Man becomes enraptured the first time he hears ragtime. This was a man who claimed once to have composed a poem, “The Creation,” while sitting on the stage at a rally. This was a man who, in the dark nadir of Jim Crow, in 1901, could write, “sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us.” To sing, to write, to create, these were essentials of life that Johnson insisted upon, and that we today celebrate. So please, enjoy.