At left: Chopin at a sound poetry performance. At right: sample dactylopoème or typewriterpoem.

General Modern has recently acquired the library and archive of the late Henri Chopin, avant-garde artist and poet (1922-2008). Following on the heels of French lettrisme, Dada, and Surrealism, Chopin is probably best remembered for his contribution to the budding discipline of “poésie sonore” or sound poetry. Among other techniques, Chopin might swallow a microphone and record the minute vibrations of the human instrument, often layered on top of other recorded sounds, producing such works as “Throat Power,” “Digestion,” and “Interplanetary Rocket.”

He used very basic equipment and often tampered with the tape path by, for example, pasting matchsticks on the reel bed to create purposeful distortions. (He would also perform his works, which is quite fun to watch; check it out here.)

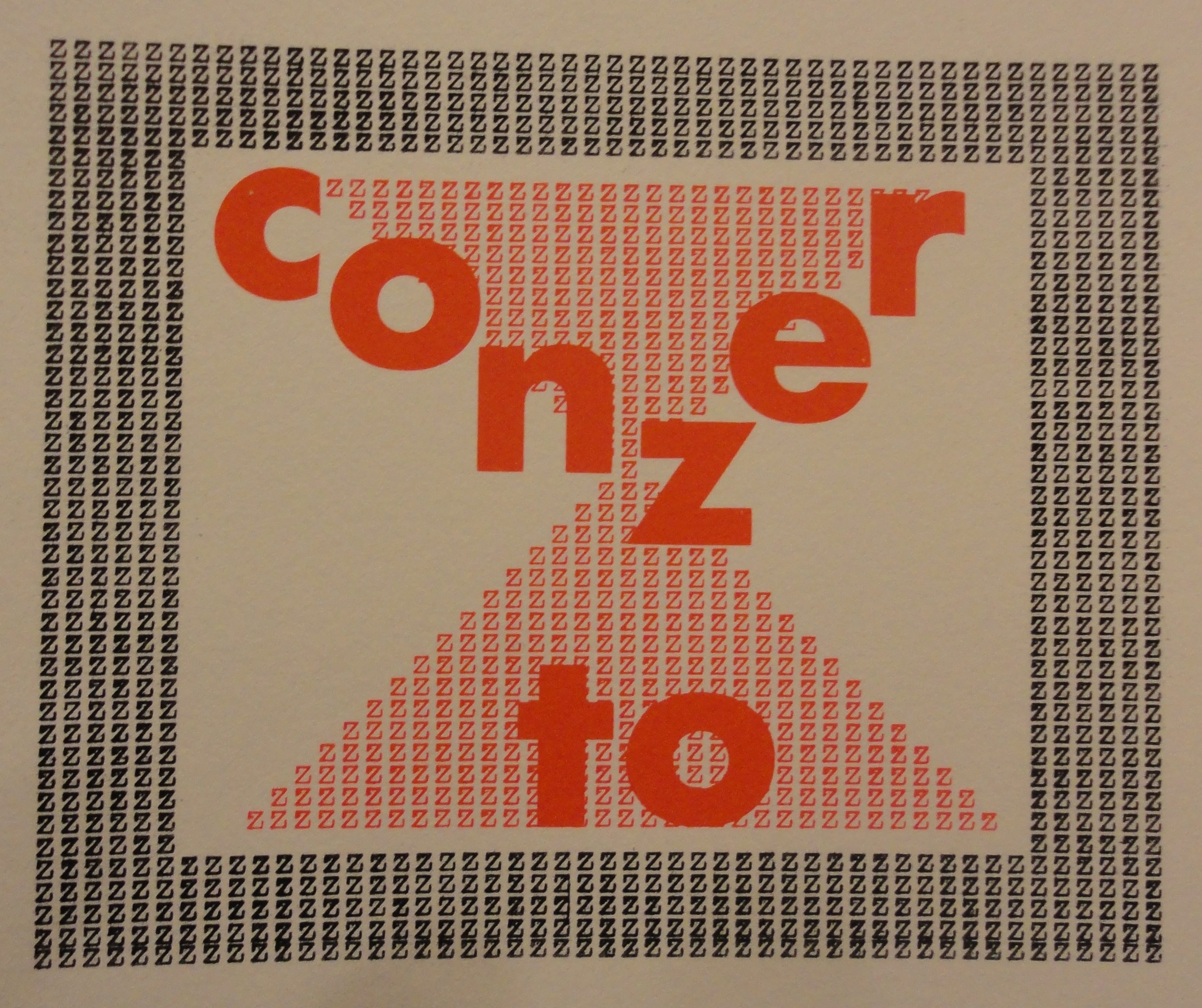

By passing the same sheet of paper through the typewriter multiple times and at varying angles, Chopin achieves this design.

But throughout his 50+ year career, Chopin was prolific also as a painter, graphic designer, typographer, and film-maker. He published dozens of volumes of his audio-visual magazines “OU” and “Cinquième Saison,” as well as many original books, collage works, installation pieces, and writings. While he was careful to remain unaffiliated with any particular grouping–he called Lettrism “a dictatorship”–and cherished his artistic independence, he nevertheless collaborated and corresponded constantly with other leading figures of the European avant-garde. A big portion of his collection are various books, letters, and art pieces dedicated to him by the likes of Raoul Hausmann, Brion Gysin, Francois Dufrene, William Burroughs and Gianni Bertini. His connections across Europe and disciplines reveals he was a major point of contact on the international post-war art scene, and through tracking this network we can index the ever-shifting preoccupations of the avant-garde.

Underappreciated in mainstream art historical dialogue, Chopin’s work plays with and challenges conventional notions of speech, language, music, sound, and semantics. His sound poems and dactylopoemes shed previously held verbal or symbolic value, to focus instead on purely sonorous or decorative qualities. The latin alphabet, he insists, “is more geometric than calligraphic for our vision,” and “consists of constructivist forms.”

An ode to the dynamism of the sound recorder, here depicted as the Paris metro in a series called “Tubes.”

By manipulating modern-age technology, Chopin seeks to access the primal expanse of communication, the infinity beyond symbolic meaning. The tape recorder makes possible the elongation and elaboration of sound shapes, makes audible the normally inaudible. Similarly, the typewriter, in its perfect repetitious typescript, showcases the “architectural skeleton” or pure form of letters and words. In this way, Chopin simultaneously engages the mysterious archaic and the mechanical state-of-the-art.

From his “Concerto en Zhopin mineur,” a simultaneous play on the “z” sound and the “z” formation.

Perhaps this interest in the intersection of modern and primal can be traced back to Chopin’s experience of the Nazi regime, with its prehistoric violent warfare and hatred in a modern technological context. After France fell under German occupation, he was captured and sent to a POW camp in the Czech Republic from which he managed to escape. After spending time with the advancing Red Army, he was recaptured by German forces and sent west on a Nazi “Death March.” It was then he discovered the power of “extra-verbal communication.” He also lost two brothers in the war, both, like him, renegade spirits who didn’t share Henri’s luck. The sounds he creates, then–from vibrating nose hairs, to farts, hisses, and labial snaps–become profound expressions of human existence, made possible, perhaps, by his very own humanity having been called into question. Beyond the obvious quirk and hilarity in his work, there lies beneath a deeply poignant creative act.

Much of his library (around 500 books) is catalogued and available for study, and his amazing archive forthcoming.