Chopin’s library contains all kinds of quirky and fascinating volumes. Many are collections of dactylopoèmes (examples of which mentioned in last week’s post) complete with wonderful titles, like: Passementeries (Trimmings), Riches heures de l’alphabet (The Alphabet’s Heyday), Folles folies des follies (The Foolish Folly of Follies), and Squelette du verbe et alentour (Skeleton of the Verb and Elsewhere). Other examples provide a colorful glimpse into Chopin’s wide network of friends, like Pour parler et pour cause, dedicated and written by fellow avant-gardist Gianni Bertini. Inside the front cover lies a check from the “Banca della felicità et dell’amore” (Bank of Happiness and Love) made out to Chopin for 365 days of happiness. In one interesting passage, Bertini compares the act of writing a poem to a butcher wrapping meat–first it is cut, blood oozing, then weighed and swaddled tightly in sturdy paper. “We wrap words so that they cannot escape.”

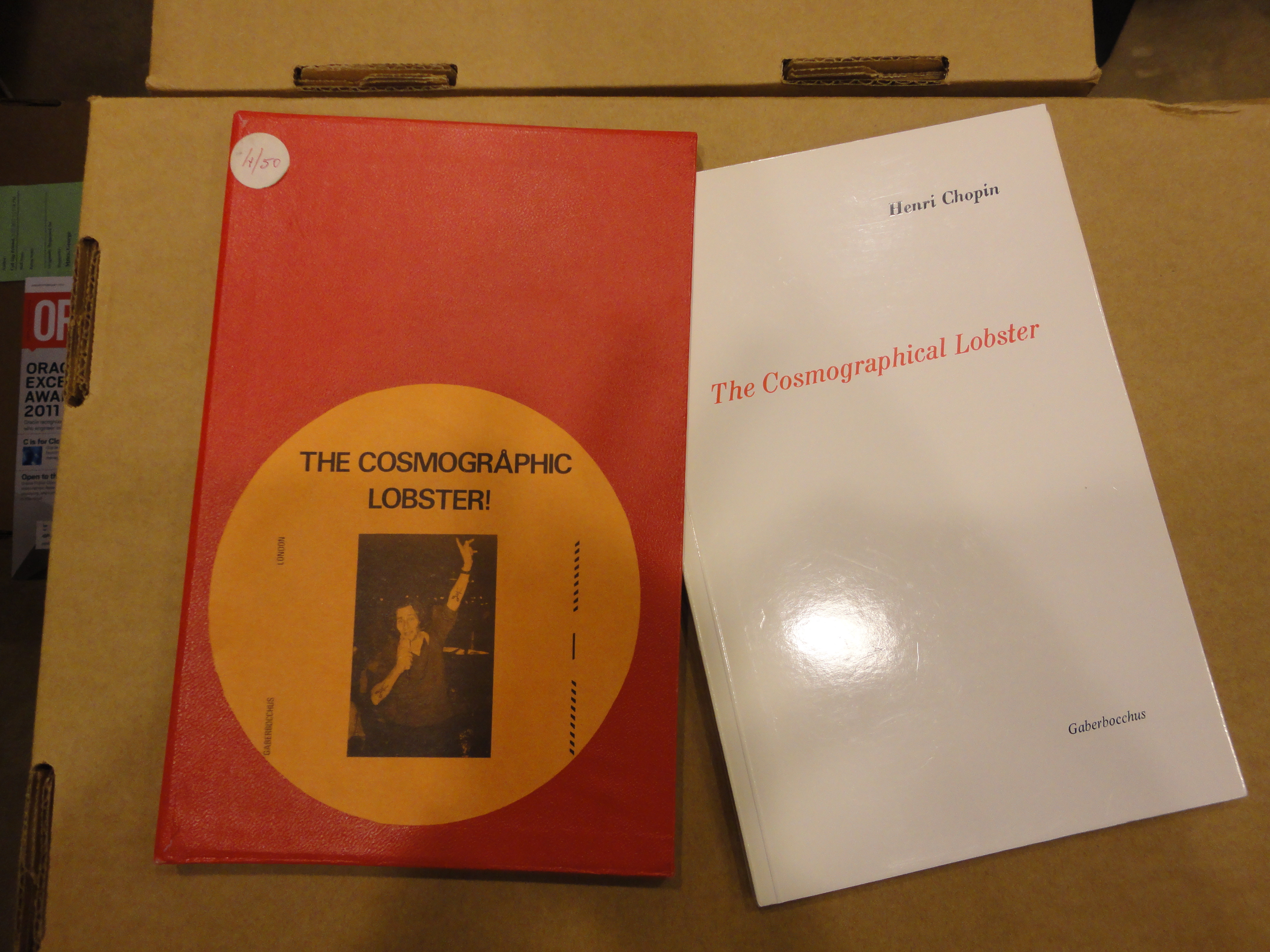

Still other books attest to Chopin’s imaginative talents and neverending stream of multimedia projects. Here a deeper look into “The Cosmographical Lobster,” a poetic novel.

The Cosmographical Lobster: slim volume and bright red sleeve

“The Cosmographical Lobster” opens with a nonsensical sum, alerting us to the novel’s playful relationship to conventional logic:

- 22 + 8 + 7 + = 987678432 + 5 + 7 + 8 = 3 + 1 + 2 + 3 + 7 + 9 + 7 = 4789765456765536543423341

- and insisting : THE ANSWER’S RIGHT.

- –

- He then goes on to introduce the novel’s key characters: ERnest (age 222222, 000000, 6666666, 888888, 4444444), the President of the World Government, and Mr. X, Governor of the Ciphered People. For eons, the Ciphered People had lived without the WORD: “The word as such was of very little account - its function, which had previously been indispensable to the misunderstanding of human beings…” The ridiculous authors who had used it, Shakespeare, Molière, Plato, were “old museum pieces.” Their favorite TV program, a masterpiece, was a “0” on a white background. For the Ciphered People there was no more need for philosophers, poets because all of metaphysics could be summed up with ” + added to - = “. ”It was strictly imperative to listen to the speech of the Head of the Universe,” writes Chopin, “but of course it was strictly forbidden to comment on it or to understand it. In any case, understand means nothing.”

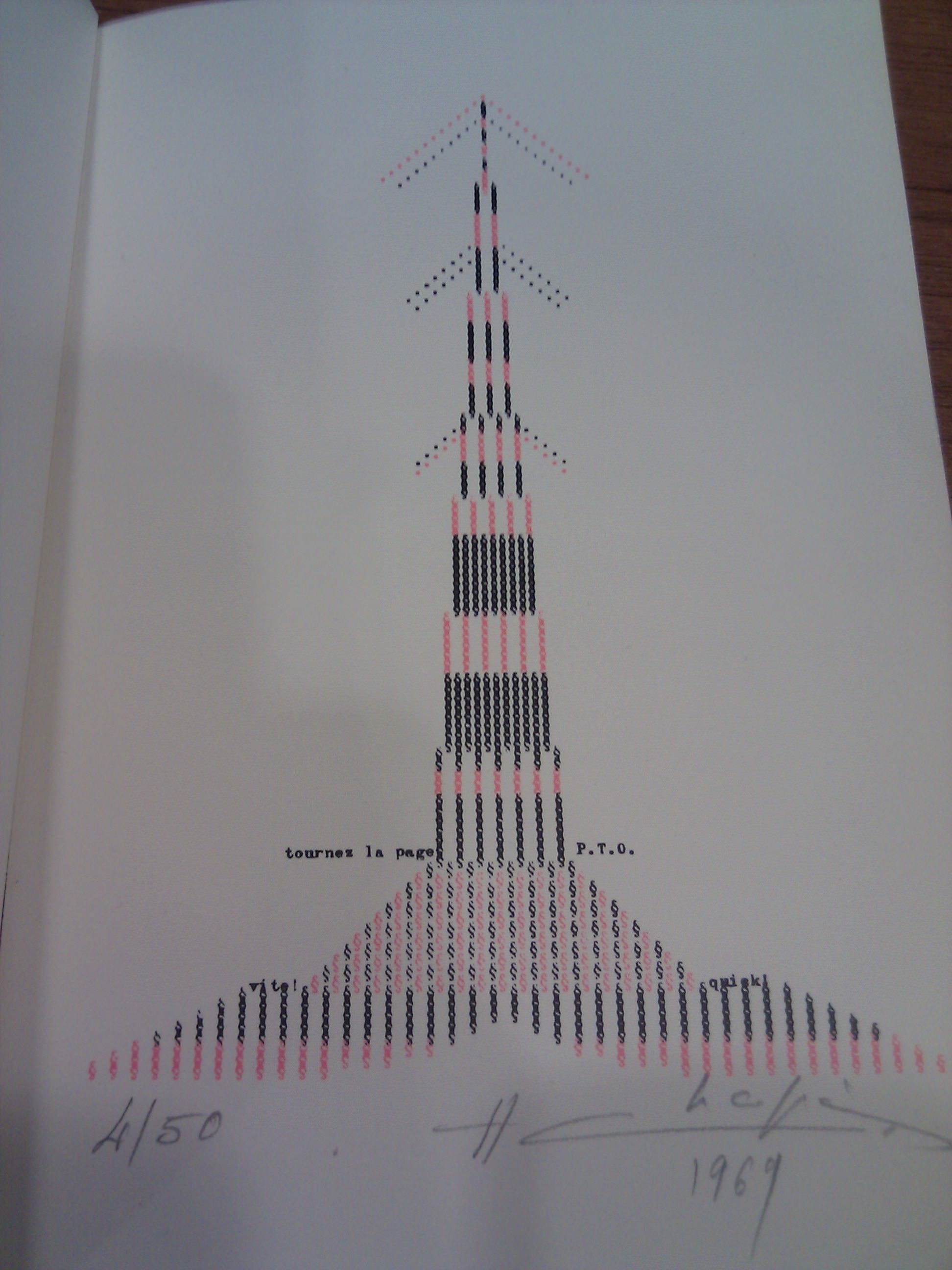

Lobster-esque dactylopoème inside front cover

But ERnest, the enlightened, craves to live once more among the Word. And so he quests to recreate the Universe because, as it is well-known, “In the beginning was the word.” With each of his succeeding thoughts and movements, ERnest regenerates the Cosmos, the Earth, and all living creatures. In a spaceship hurdling through time and space, the difficult voyage continues oward the rebirth of the word, attempting to reverse the damage of history: “Humanity, that had become dumb in the twentieth century, was thrilling to life once more.” At last, the final proclamation: “THE SOUND OF THE UNIVERSE WAS HEARD.”Throughout the novel, Chopin strings together entire paragraphs without spaces, spells words backwards, launches into rhyming tangents, makes verbs out of friends’ names (heidsiecking, gysinning) and employs scattered spacing, among many other puns and disruptions. Naturally, the loose “narrative” is often occluded and hard to follow. But it is a fun meditation on humankind’s simultaneous devotion to and repugnance for language. The Word is at once fundamental to the universe and completely meaningless, a theme undoubtedly present in his sound poetry and typewriterpoems. It seems Chopin also makes reference to the terrible power of language to influence the masses; he saw firsthand how propaganda and political rhetoric had ended in catastrophe in the 20th century. Perhaps, then, The Cosmo Lobster is a cautionary tale: we must be careful with words and appreciate the sounds proferred in the universe, lest we lose them.