View 25 illustrated book covers from the Beinecke Library’s collection

View 25 illustrated book covers from the Beinecke Library’s collection

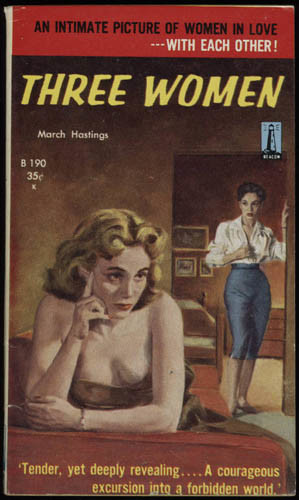

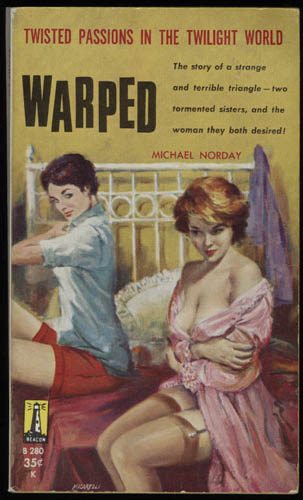

Lesbian Pulp Novels

By Anastasia Jones (PhD candidate, Yale Department of History)

Comprised of several hundred titles that sold, collectively, into the

millions, lesbian pulp fiction flourished between 1950 and 1965. The genre’s so-called Golden Age was but a small segment of the paperback phenomena that swept America during and after World War Two. Beginning with Pocket Books’ 1939 birth, paperback publishers capitalized on their established magazine distribution networks to sell pulp fiction on rotating racks in drugstores and gas stations around the country. The postwar paperback trade was, in some ways, an organic continuation of the pulp press—penny dreadfuls, comic books, and magazines of sensational serialized fiction—that had flourished fitfully from the turn of the century. Yet it is an error to read postwar paperbacks as merely derivative. Small enough to fit into a back pocket, these slim fictional volumes were nothing short of a new cultural medium. They were printed and sold cheaply, so readers could, in pulp author Ann Bannon’s estimation, afford to enjoy a book on the bus and leave it on the seat. The content, however, was enthralling enough to make the tiny tomes worth holding onto. Though sometimes reprints—resulting, incongruously, in The Iliad jazzed up with a breathless blurb and a sultry dame—postwar paperbacks were often original novels that heralded the birth of new genres.

These fledging genres were bound by a nearly universal emphasis on broodingly erotic sensationalism. Teenage drug addicts, corrupt private eyes, nudist alcoholic housewives—and, of course, lesbians—joined a newly sexualized cultural landscape, roaming their melodramatic fictional milieus of illicit alleyways and deviant suburbs. This almost giddy cynicism revealed hidden social anxieties, deftly exposing the soiled underbelly of the American Dream’s gleaming postwar topcoat. But unlike unspoken doubts, paperback fiction was forever in the public eye. In short, the books sold—from thousands, to, in some cases, millions of copies. Further, pulp fiction books and publishers were embroiled in an extensive series of popular and legal battles over censorship and pornography well into the 1960s; these debates sold newspapers and filled courtrooms. A phenomenon was afoot.

Lesbian pulps formed their own distinctive category within the wider medium, but the genre is not easy to define, nor are its borders obvious. For one, because sales figures are not readily available, it is impossible to pinpoint readership. This imprecision complicates the usual division made between the “lesbian-friendly” subgenre—around a dozen titles, subject to scholarly attention and frequent reprints by feminist presses—within the tawdry horde, written, it is claimed, “for men and by men” to fulfill straight men’s fantasies. For instance, Vin Packer’s (Marijane Meaker) 1952 effort for Fawcett Gold Medal, Spring Fire is beloved in lesbian circles for its generally insightful and sympathetic portrayal of the vaguely butch-femme sorority romance between Mitch and Leda. Far from negotiating a secret path of veiled rebellion through what is commonly seen as a misogynistic and voyeuristic genre, though, Meaker’s book was an acknowledged superstar; apparently selling over one million copies, it—along with the 1950 bestseller, Women’s Barracks—kick-started Fawcett’s immediate foray into the genre. In short, it was not simply closeted lesbians in New Jersey purchasing the novels. Nor is authorship necessarily clear. Use of pseudonyms was rampant (delightfully and confusingly, men frequently too k on female aliases, while women sometimes wrote under male names), and false autobiographies and fake journalistic (or vaguely sociological) “exposes” abounded. Writers frequently wrote for several publishers, and, for that matter, under the veil of several genres. Moreover, the genre swings somewhat wildly—frequently within the pages of a single book—between gratuitous scenes of gang rape and sentimental depictions of lasting lesbian relationships, between humor and misogyny, romance and alcoholism, bliss and rampant self-hatred.

k on female aliases, while women sometimes wrote under male names), and false autobiographies and fake journalistic (or vaguely sociological) “exposes” abounded. Writers frequently wrote for several publishers, and, for that matter, under the veil of several genres. Moreover, the genre swings somewhat wildly—frequently within the pages of a single book—between gratuitous scenes of gang rape and sentimental depictions of lasting lesbian relationships, between humor and misogyny, romance and alcoholism, bliss and rampant self-hatred.

Still, for all its variations, constants emerge. Plots were, for the most part, standard: the everygirl, disillusioned with romance, suffers at the hands of the impersonal and coolly libidinous world, but finds, finally, love—in the arms of a man or a woman. On a more thematic level, questions surrounding convention, identity, masculinity, belonging, and, especially, female desire flowed from the pens of countless authors, and span across disparate titles and publishing houses; these anxieties and hopes—this fascination—formed the genre’s molten core.

The covers, meanwhile, provide their own sort of ballast. Authors frequently complained that the illustrations rarely matched plots. But if they don’t correlate, precisely, to the stories within, they do connect to each other; they are a cohesive body of sultry (feminine) “butches” and cowering negligee-clad femmes, of Greenwich Village street corners and meaningful glances, and paranoid and lustful blurbs. The covers, to be glib, are not all the genre has to offer. But in their uncanny mix of sex and anxiety, in the foggy blur they made of borders between heterosexual and homosexual desire, and in the breathless trajectories they spanned between deep-seated cultural fears and shallow escapist pleasures, they offer a suitable introduction to a compelling and perplexing genre.