Lost Play Found:The ‘Exorcism’ Of Eugene O’Neill

by NPR Staff; reposted from NPR.org, March 25, 2012

Exorcism A Play in One Act, by Eugene O’Neill, Edward Albee and Louise Bernard

“Oh, no, no,” Washington Post drama critic Peter Marks wrote recently. “Not Eugene O’Neill.”

Marks was reacting to an ambitious O’Neill festival underway at various theatres in Washington, D.C. To many, O’Neill remains the quintessential playwright of miserable people in miserable families leading miserable lives full of misery. And booze.

Yet he was an American master, winning four Pulitzer Prizes and the 1936 Nobel Prize. Even an early work written two decades before more famous plays like Long Day’s Journey Into Night and The Iceman Cometh — one long thought lost, and recently rediscovered — shows his skills.

Drama Fellows at Arena Stage have been rehearsing that long-lost play, Exorcism: A Play in One Act, written in 1919 when the playwright was 31. Twenty-something actors Enrico Nassi and David Olsen play down-at-the-heels chums living together in a tawdry New York rooming house in 1912. One character — Jimmy — has been dumped by his wife. The other — Ned — was kicked out by his wealthy father. Ned is desperate.

“After hitting rock bottom, he decides to take his life,” says Nassi, who plays Ned. He’s saved by Jimmy, played by Olsen.

“It’s autobiographical,” says Olsen. “It’s based on a real experience O’Neill had when he was in his 20s.”

Having survived the suicide attempt, O’Neill turned to writing. “I believe in the introduction to the play it says he traded the romance of death for the romance of art,” says Olsen.

During a public reading of the one-act play, the actors rehearse dialogue O’Neill wrote in 1919. Olsen says O’Neill is the playwright who first put American vernacular onstage. “It translates fairly well,” Olsen says. “We can connect with it.”

Nassi agrees, saying, “It’s so rich. It’s so full.” The young actors like O’Neill’s period-specific colloquialisms, such as “tenspot,” “wiseguy” and “talking rot.” They say the language takes you to a different time and era, yet it’s crisp, clear and understandable.

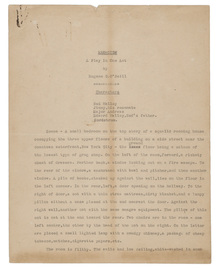

Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript LibraryExorcism, an O’Neill play thought to be lost forever, was recently unearthed in manuscript form. O’Neill’s second wife had sent it to a friend as a Christmas gift.

Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript LibraryExorcism, an O’Neill play thought to be lost forever, was recently unearthed in manuscript form. O’Neill’s second wife had sent it to a friend as a Christmas gift.

Exorcism may not be a great work, but its themes — struggles with family, with self and, yes, with misery and booze — are among those that would be developed as O’Neill did. When the playwright died in 1953, he was a dean of American theatre. That makes Exorcism a kind of portrait of the artist as a young man.

O’Neill destroyed every copy of Exorcism after the play was performed in 1920 — or he thought he did. For more than 90 years, Exorcism was believed to be lost forever. Then Yale’s Beinecke Library got a call from a dealer who said he had a copy of the manuscript. He’d bought it from the estate of a screenwriter named Philip Yordan.

Louise Bernard, the Beinecke Library’s curator when the lost manuscript turned up, explains how Yordan got the manuscript.

Yordan was a friend of O’Neill’s second wife, Agnes Boulton. “After her divorce from O’Neill, she had apparently kept manuscripts that she perhaps wasn’t supposed to keep,” says Bernard. “[Boulton] decided to give this particular typescript of the play Exorcism to Mr. Yordan. She sent it apparently as a Christmas gift. It emerged again in its original brown envelope with Christmas stickers on it.”

Why exactly O’Neill destroyed all his copies of Exorcism remains open to interpretation, says Bernard. “Obviously, it wasn’t his finest work,” she notes. “He was still very much an apprentice playwright at this point.”

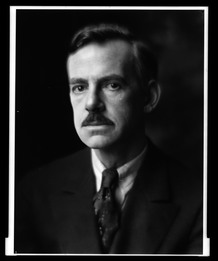

Eugene O’Neill is the author of canonical American plays such as The Iceman Cometh and Long Day’s Journey Into Night.

Eugene O’Neill is the author of canonical American plays such as The Iceman Cometh and Long Day’s Journey Into Night.

However, O’Neill won his first Pulitzer only a year after Exorcism’s production. Another theory about why O’Neill buried Exorcism centers on the play’s confessional nature.

“He was really revealing very personal things about his life,” says Bernard. “This was something he perhaps regretted. His father was dying at the time the play was first produced. And so I presume that he chose to hold back on that kind of very personal detail.”

O’Neill was often reluctant to release his work to the public. After all, his masterwork, Long Day’s Journey Into Night, was never produced or published in the playwright’s lifetime. This raises moral questions about putting on Exorcism now, in 2012. If O’Neill was so adamant that the work be forgotten, is this revival doing him a disservice?

“It’s an important ethical question,” says Bernard. “Certainly we have to take into consideration the rights and feelings of the creator of the piece. But at the same time we can also place this particular play in a very rich context … We’re able to appreciate this with great hindsight in a way that O’Neill himself may not have been able to.”

The Eugene O’Neill Festival in Washington, D.C. runs through May 6th.

The book: Exorcism A Play in One Act, by Eugene O’Neill, Edward Albee and Louise Bernard

More on this book at NPR: NPR reviews, interviews and more