The Beinecke has recently acquired new Orson Welles materials, including an unproduced screenplay, the original script of a 1943 film, and a second draft of Welles’ famous film Citizen Kane with accompanying notes. These new documents join the Beinecke’s collection of papers related to Welles’ unfinished feature film, It’s All True. Descriptions and links can be found below.

Orson Welles (1915-1985) was an American actor, director, producer, and writer. He is best known for his 1938 radio adaptation of War of the Worlds, his 1941 film Citizen Kane, and his 1942 film The Magnificent Ambersons.

Scholars who are interested in Welles’ creative process, artistic depictions of fascism and 20th century world politics, ethnicity, race, and migration studies, or colonial and postcolonial art and text will find these documents engaging and fruitful.

***

“Everything must move at the same time” - Mr. England in The Way to Santiago

“We should have made of the past a mirror with which to see round the corner that separates us from the future. Unfortunately it no longer matters what we could have seen. We are returning the way we came” - Haller in Journey Into Fear

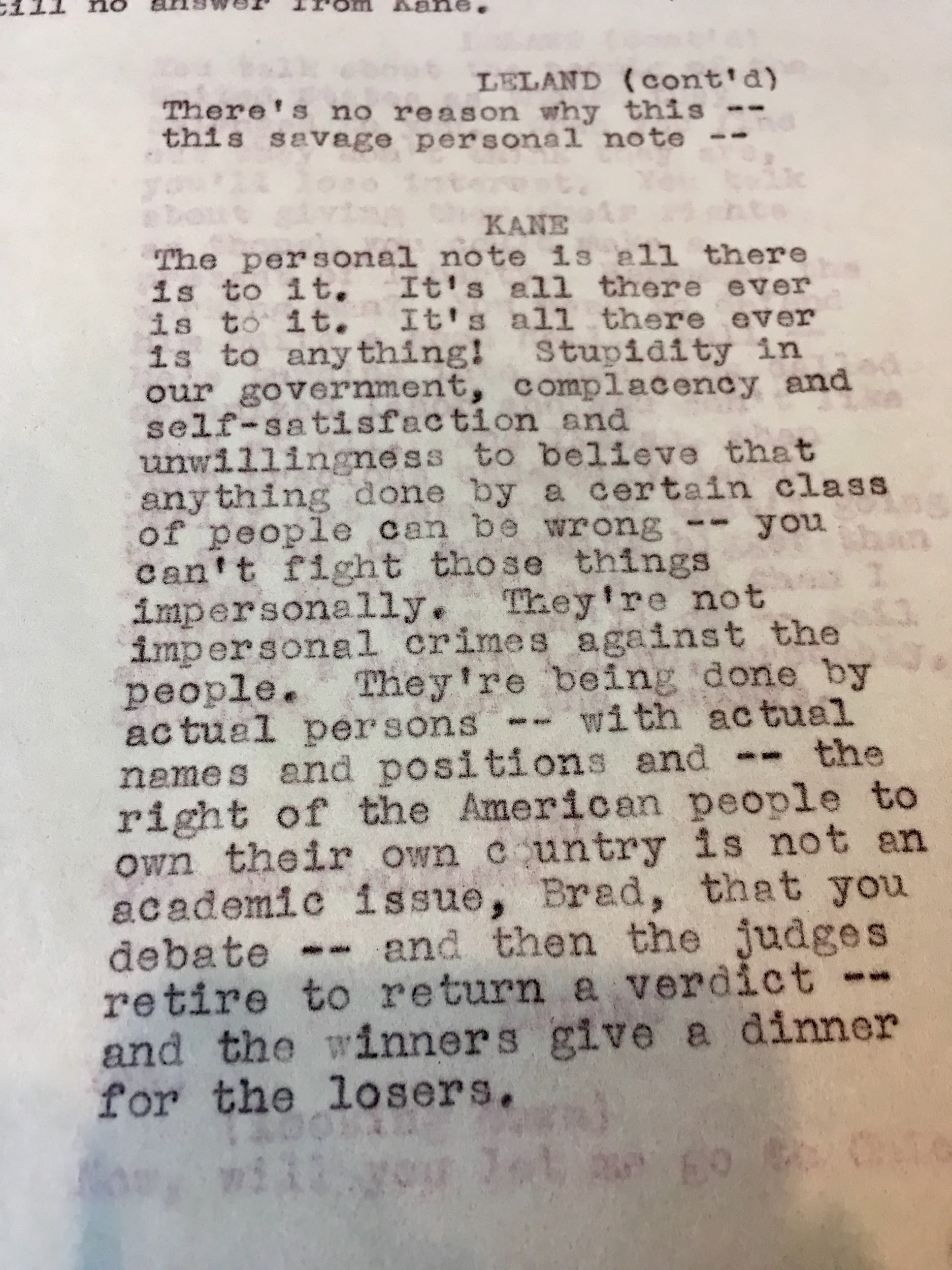

“The right of the American people to own their own country is not an academic issue….that you debate” - Kane in Citizen Kane

***

Orson Welles #4 [The Way to Santiago]

Masquerading as a bound collection of pale, soft, blue and green pages, The Way to Santiago is deceptive both in form and in content. Filled with revolution and Wellesian suspense, the work emphasizes the mistranslations and manipulations which guide human interaction and connection. Throughout the screenplay, tourists encounter native peoples, fascists encounter anti-fascists, men encounter languages, and languages encounter men (and occasionally, women). A love story somehow survives the chaotic and violent plot.

The script was adapted from Arthur Calder-Marshall’s 1940 novel of the same name (see The Way to Santiago in Orbis: http://hdl.handle.net/10079/bibid/5409983) and was never produced, despite Welles’ description of it as a “Mexican melodrama” and his “best popular story.”

Centered around themes of translation, memory, and political mythology, the story unearths the ways in which people from around the world are simultaneously near to and distanced from one another. The screenplay presents the forged and real boundaries between individuals, languages, and races, presenting to an audience the fragility of empathy and the ways in which politics can distort our views of the self and our views of others.

Anti-fascist rhetoric emerges throughout the script. Elena, the female protagonist, is on the anti-fascism side of the revolution. She says fascism means “tyranny. It means everything that isn’t human or beautiful. It means – it means the ant hill. – Darkness and death.”

To read more about Welles relationship to fascism and race relations, see his 1944 article, “Race hate must be outlawed”: http://www.wellesnet.com/orson-welles-race-hate-must-outlawed/

The screenplay’s narrative hearkens back to the historic cry of Roman Catholic priest Hidalgo in 1810, a cry which sparked the Mexican War of Independence. The Way to Santiago ends with the protagonist’s voice echoing across the world, from a Mexican bar to an American family room: “Here’s another Grito. I hope it will be heard.”

Scholars may want to explore why this script was ultimately abandoned, how the text describes and resists fascism (perhaps in comparison to texts written post-WWII), and questions of race, ethnicity, and Otherness.

“Civilians are the architects of peace” –Orson Welles

Journey into Fear

Set in Istanbul and Alexandria, Journey Into Fear begins as a narrative of domesticity and quiet, though violent, intrigue—a man bathing, a husband and wife separated, a magician shot in the dark during his act; the script was based on the novel by Eric Ambler (see the novel and photoplay in Orbis: http://hdl.handle.net/10079/bibid/13194065 & http://hdl.handle.net/10079/bibid/11194625). The script descends at a crescendoing pace into chaos, with shot after shot of men chasing one another, women standing nearby in confusion and naivete, and bodies and weapons falling off buildings and cascading to the street below.

The script follows men with opposing languages, manners, and cultures as a means of capturing the intricate web of international relations in the Middle East. Of course, the script is told through an American lens, placing America’s diplomatic policies at the center of the global affair.

The 1942 film was shot almost entirely inside RKO Studios, and Joseph McBride, American film historian and writer, described Journey into Fear as “‘at best a very rough draft for some of Welles’s later films.’” (At the End of the Street in the Shadow: Orson Welles and the City, Matthew Asprey Gear, 2016).

This text is especially interesting for researchers who wish to explore textual drafts and the ways in which works change over time–versions of the film with differing amounts of censorship were released in April 1942, August 1942, and October 1942. Scholars focused on the auditory in works of written and performed theatre will find an abundance of sound, song, and voice in both The Way to Santiago and Journey into Fear.

Orson Welles notes and screenplay relating to Citizen Kane

Folder 1: “Notes on first draft scripts of ‘Kane’” April 30, 1940 - May 2, 1940

Welles’ notes comment on scenes and characters of the ‘Kane’ script, revealing his thoughts about and intentions behind process, narrative structure, images, language, and enigma. Welles describes in detail the relationships between characters and the life of characters before they enter the world of the script, information untold in the select bursts of dialogue throughout the text itself.

A few excerpts:

Welles illuminates that he added a scene between Kane and his ex-wife, Susan, to introduce a “woman-element to tide us over the necessarily masculine and action sequences.”

“Bernstein represent in Kane’s life the newspaper, pure and simple — the period in Kane’s life when he was functioning the most effectively and the least complexly.”

“The Emily story is, frankly, a narrative — a sequence of events telling the story of ten years in a man’s life….The scenes on the lake are frankly and deliberately Bob Montgomery-lyric, silly, smart, boy-and-girl stuff. The beginning of the rift — the cliched story of the American husband whose wife sits home while he does man’s work at the office is deliberately cliched.”

“Susan is probably the most important character in the picture and very special attention has been given to the manner of her introduction.” Welles then outlines the preparation that precedes Susan’s entrance, saying it is “contrived.”

Folder 2: Screenplay, “2nd Draft continuity” May 16, 1940

153 Scenes; changes stamped across the cover from May 1940 - June 1940

The script begins with a heightened attention to the visual, to light and object and space. The screenplay is one of memory; Kane’s past is perused in an attempt to figure out how to posthumously portray his life in a movie short. The present-day characters are also attempting to uncover the origin of Kane’s last word: “Rosebud.”

The screenplay begins briefly with his childhood and travels through time, sometimes back and forth through time, imagistically. When physical newspaper articles appear on the screen, the camera “follows the words with the same action that the eye does in reading.” The entirety of the work mirrors this sentiment; Kane’s life is illustrated realistically and sincerely, as if the audience were watching time pass by with their own eyes.

Some scenes in the manuscript are marked as unfinished:

The text explores ideas of free speech and fake news, truthful journalism and civil rights. Ultimately, the screenplay demonstrates the disintegration of idealism.

***

Papers relating to It’s All True

Orbis link: http://hdl.handle.net/10079/bibid/12960669

It’s All True was supposed to be Welles’s third RKO film. The feature film was inspired by conversations between Welles and Duke Ellington and was planning to include sections on the history of jazz, but the film ended up being cancelled by RKO. The unproduced film was the subject of a 1993 documentary, It’s All True: Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles.

Included in these papers are the unproduced script sections, “Love Story” and two drafts of “My Friend Bonito,” intended to be parts of the four-part film and written by John Fante and Norman Foster in 1941. Also included is a report on the Carnaval sequence of the film, a breakdown of the scenes of It’s All True, treatments of the connecting scenes of It’s All True, and legal papers concerning the cast and crew of the production.

“Love Story” begins, “This is a story of simple people. It begins when your mother and mine were girls. It teaches no moral and proves nothing.” The story is about two working-class young people who fall in love, a “dark” Italian man named Rocco and a young woman named Della. Scholars may be interested in the script’s conscious dealings with class politics.

“My Friend Bonito” is about a little boy in Mexico named Chico and a fighting bull named Bonito. The script claims: “A bullfight is not a contest between man and best; it is a predestined tragedy. All bulls die, as all men die.” The script details the life of Bonito from his birth to his last bullfight and appears to be a silent film, or at least a film without spoken dialogue, up until the crowd’s cheers in the final scene.

The box includes a later draft of “My Friend Bonito,” used as the shooting script in September, 1941. The revisions are significant.

The 1942 Carnaval report is perhaps the most interesting of the documents, as it rigorously details the processes of writing a script, engaging with new ideas, gathering props, selecting actors, and creating film sequences. The report details Welles’s opinions at meetings throughout the creation process and explicitly states that Carnaval would be “shot off the cuff.” The report also spends a lot of time discussing the music of the film.

A 1943 document contains a break-down of the scenes of the feature film and physical notes about the production. Each scene lists the amount of dialogue which will be spoken (half a page, three pages, etc), the Principals, the Extras, and notes about set and props. The skeletal document will be incredibly interesting for scholars interested in Welles’s creative processes of construction and deconstruction.

Another 1943 document included in this collection is a general treatment of the connecting scenes of It’s All True. The treatment begins with a note by Orson Welles about narrative structure and storytelling:

The final document in the box lists the RKO Company and the passport statuses of each actor and crew member. The folder also includes the 1941 RKO Radio Pictures, Inc. Agreement, legal documents concerning salaries, and a note from Louis Armstrong to Joe Glaser allowing Joe to sign any and all papers for him pertaining to the Orson Welles picture.

***

All of the Beinecke’s Orson Welles related collections reveal the mind and process of Orson Welles as he created. The stage directions and instructions which litter the text—notes about camera angles, purposeful shadows and light, characterized breaths, meticulously described glances—are invisible to a film audience’s discerning eye. Reading these manuscripts will reveal these invisibilities.