In 1909, the founder of Futurism, an Italian literary and artistic movement, Filippo Tommaso Marientti published his first novel, Mafarka le futuriste: roman africain. An epic tale following the trials and battles of Mafarka, the King of an imagined Africa, the novel concludes with the realization of his mechanical son, Gazourmah. Initially the book was only of interest to literary and artistic circles, however the sexually explicit scenes of rape, violence, and death soon led the Italian State to bring legal charges against the newly published text, thrusting it into the national spotlight. Accused of “oltraggio al pudore” (offense against modesty), the book faced censorship. Though the trial resulted in an acquittal, it exposed Futurism to the large audience of writers, artists, journalists and students in attendance and the event is now considered one of the first major public happenings of Futurism.

Despite its polarizing reception, the novel remains one of the foundational texts of the Futurist movement. Moreover, the character of Gazourmah remained a model for the artificial yet living beings who populated the vast range of media produced by Futurist artists—including paintings, collages, sculptures, photographs, toys, marionettes, plays, poetry, and prose. The Futurist visualisations of the machine aesthetic personified in corporeal form express a collective desire for a mechanized man. It is the goal of my dissertation to provide the first cohesive study of this figure in Italian Futurist art and literature.

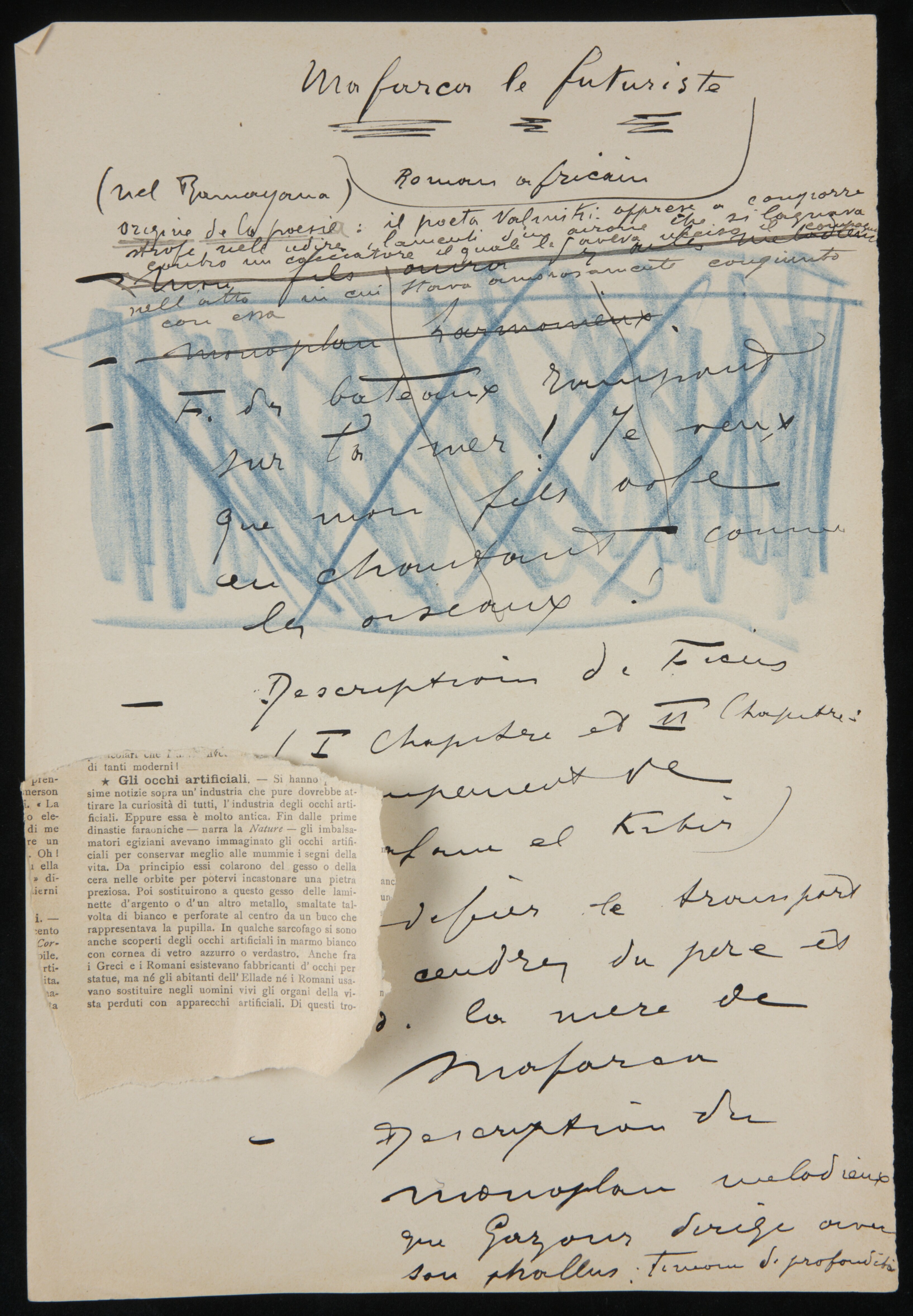

As the holders of a substantial portion of Marinetti’s personal archive, the Beinecke’s collection provides some of the key materials for the investigation of this topic. The Filippo Tommaso Marinetti papers (MSS GEN 130) hold a variety of useful documents that provide clues on the evolution of the artificial yet living being in Futurist literary and artistic discourse, including the original manuscripts of Mafarka. Within these drafts Marinetti cut and paste articles, poems, and novels that influenced his writing.

Mafarka le futuriste, GEN MSS 130, Box 27, Folder 1384.

“Artificial eyes. — We have news about an industry that should also attract everyone’s curiosity, the artificial eye industry. Yet it is very old. Since the early Pharaonic dynasties—tells the story of Nature—the Egyptian embalmers had imagined the artificial eyes to preserve the signs of life better to the mummies. At first they painted gypsum or wax in urine to be able to embed a precious stone. Then they replaced this plaster with silver or other metal sheets, sometimes white enamelled and perforated in the center by a hole that represented the pupil. In some sarcophagus, artificial eyes in white marble with blue or greenish glass cornea have also been discovered. Even among the Greeks and Romans there were eye-makers for statues, but neither the inhabitants of the Hellas nor the Romans used [these eyes] to replace the lost organs of artificial devices in living men…”

One such document is found on the first page of one of the Mafarka manuscript drafts. A ripped-out portion of a newspaper article, the text discusses the origins of the artificial eye industry dating back to the Egyptians. The end of the text hints at the use of artificial eyes or organs as replacements for those damaged in living men. The inclusion of this text fragment speaks to Marinetti’s interest in contemporary scientific innovations in the field of prosthetics and in the evolutionary theories of figures like Jean Baptiste Lamarck. Furthermore, it is worth noting that Gazourmah is later realized in Marinetti’s text as a combination of organic and inorganic parts, all fabricated through artificial means.

Sophia Maxine Farmer is a doctoral candidate in art history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She earned her B.A. in Art History and Visual Studies from the University of Toronto. Her current research focuses on the intersections between science-fiction and art history as well as on conceptions of gender and identity that affected the production of artworks in Italy during the twentieth century.

***

The Beinecke Library encourages scholars, students, and the public to engage the past in the present for the future. In the service of new scholarship, the library offers generous fellowships for visiting scholars and for graduate students to support research in a wide range of fields. Learn more about fellowship opportunities.