The Sword Went Out to Sea: An Unpublished Novel By H.D.

The Sword Went Out to Sea, co-edited by Cynthia Hogue and Julie Vandivere. (Gainsville: University Press of Florida, 2007). Order from the press; order from Amazon.com.

The Sword Went Out to Sea, by modernist poet H.D. (the nom de plume of Hilda Doolittle, 1986-1961), drawing from the 1942-1946 spiritualist séances that she conducted during and following WWII, is forthcoming in a first edition from University Press of Florida in September 2007, co-edited by Cynthia Hogue and Julie Vandivere. At the Beinecke, there are three marked typescript “drafts” of The Sword Went Out to Sea, held in the H.D. Papers in the Yale Collection of American Literature at Yale University. For this first edition of the novel, we used the typescript marked “third typed draft” (YCAL MSS 24, Box 26, folders 729-734, and Box 27, folders 735-737). These three drafts are quite similar, especially Drafts II and III, and they are not dated as revisions. Indeed, all three drafts bear the dates of composition (1946-1947) rather than the dates of the revisions (1948-1950). We retained those dates in our edition, as H.D. wished Sword to bear, as follows:

Book I, Part I: 6 December 1946

Book I, Part II: 6 May 1947

Book II: 17 July 1947

For the purposes of critical placement of Sword in H.D.’s oeuvre, we dated both the composition and revision of the novel by tracking her references to it in correspondence held in several collections at the Beinecke (H.D. Papers, Bryher Papers, and the Norman Holmes Pearson Papers).We also worked with H.D.’s unpublished memoirs (H.D. Papers).

Sword is an ambitiously structured novel, and as we were able to document from our research in the unpublished papers and the published correspondence, it had been completed and polished and readied for publication, although for various reasons—that, as we argue, the vision was too non-linear, the prose too insularly encoded—H.D. never found a publisher. Despite H.D.’s conviction of its significance, and its paving the way for her late, long poem, Helen in Egypt, begun in 1952 during the year after Sword’s final revision, it has never been viewed as a discrete work with its own importance, or as meriting anything other than scholarly publication. Although few novels are as densely or symbolically threaded as Sword, we propose that it be approached initially as a testament to and working through of a grief that is generational and gender-specific: the grief sustained, repressed, sublimated by the generation of women who saw two world wars and were called “shrill” or mad or both when they tried to protest that war is mad. It is a grief sustained over the all-encompassing devastation of World War II, including the genocide of Jewish and other civilian populations, and dropping the atom bomb on Japanese civilians. We argue, after working so extensively with this novel over the course of four years, that it is indeed a mad grief—something that looks like madness but isn’t, something that is closer to fury.

The Sword Went Out to Sea comprises an incredible effort to rise from sorrow, but also, like her other writing at this time, to reclaim female agency in order to alchemize the “hawk” of war into the “dove” of peace. As H.D. writes in an earlier Spiritualist novel, Majic Ring (an unpublished roman á clé with the same characters), “ ‘blessed are they that mourn’ for sometimes peril and depression sharpen or clarify the inner perceptions and we ‘dream true’ ”(MR, YCAL/Beinecke). Although Sword’s writing is, finally in our estimation, less compelling than H.D.’s best poetry and prose, we contend that it can take its place as part of a body of women’s literature written around WWII the collective concerns of which—the destructivity of nationalism, the need for a “feminized” vision to be heard in the public sphere, among others—are helping us to reorient and reconfigure modernism. (CH)

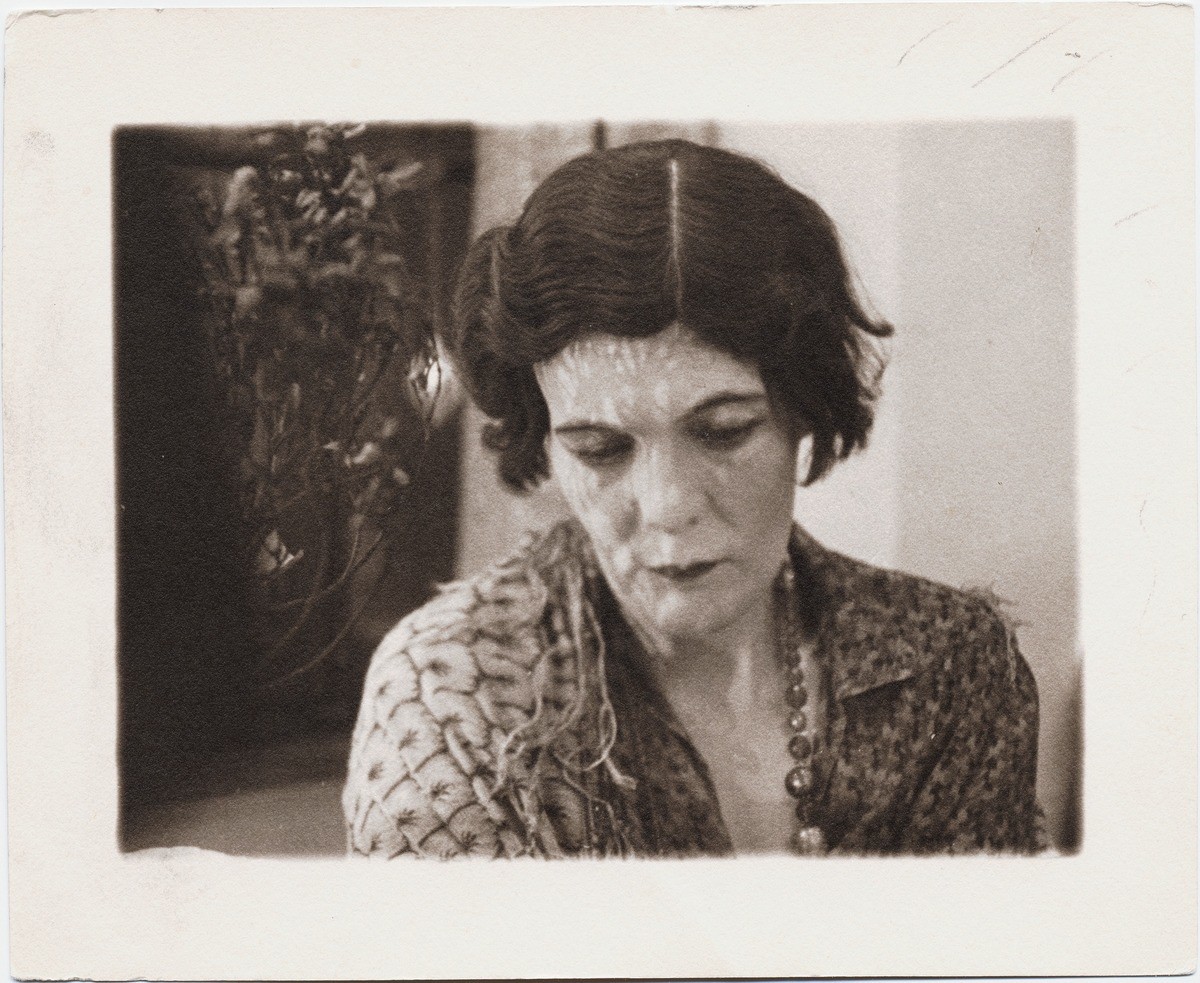

Image: Photograph of H.D.