By Raffi Donatich, Y’2019

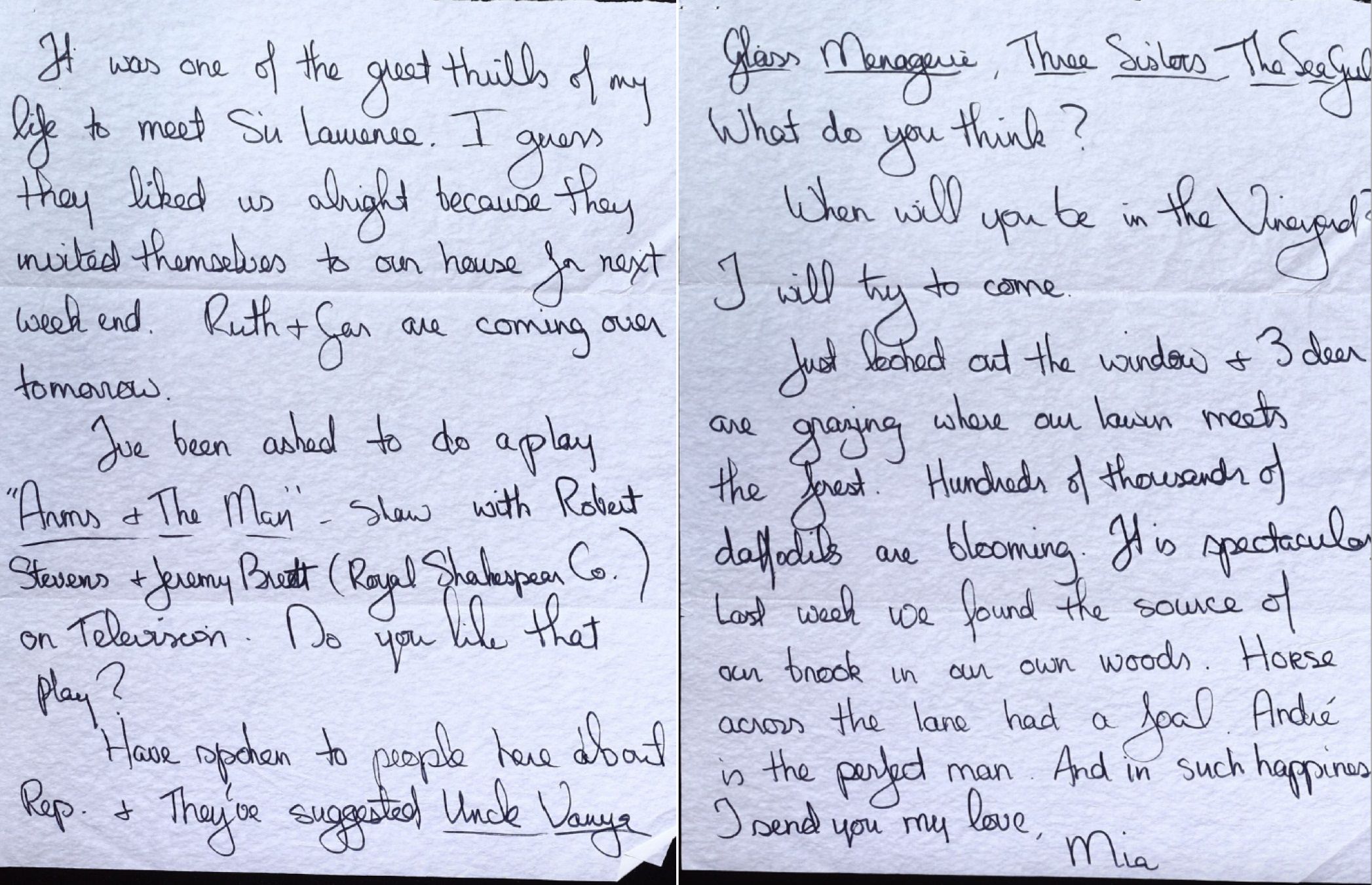

After the release of Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby in 1968 and her husband Frank Sinatra’s delivery of divorce papers on the set of that very film, actress Mia Farrow decided to take a trip. Ruth Gordon, who played the role of Minnie Castevet in the film, invited Farrow to come to her and her husband Garson Kanin’s home in Martha’s Vineyard. Gordon maintained a close relationship with renowned playwright Thornton Wilder, whom she also invited to the Vineyard. There, Farrow and Wilder struck up an unexpected friendship that continued via correspondence. Farrow, who addressed Thornton as “Thornyberry,” looked to him for sound advice for her acting career: which plays he adored, which plays he thought little of, and which roles he felt were dynamic and compelling enough to accept. The tone of their letters express sincere interest in each other’s opinions and lives: Mia letters convey her genuine desire for Thornton’s approval of her acting projects, and Thornton’s responses convey his generous investment in both her success and artistic fulfillment.

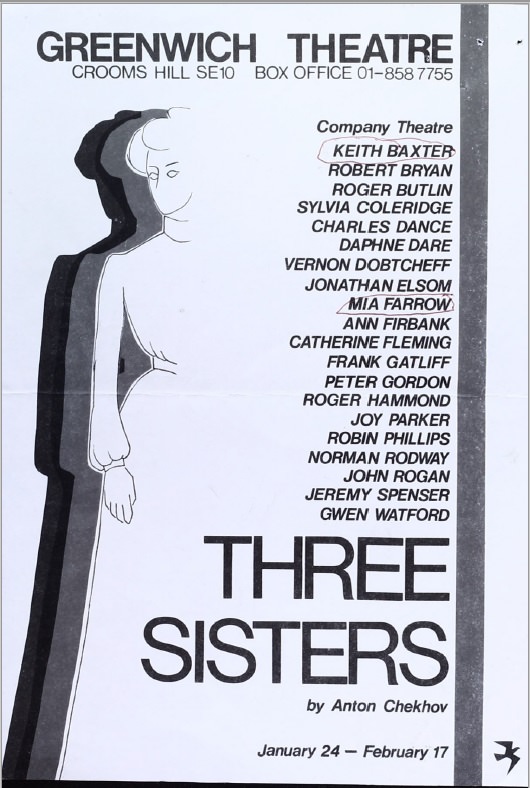

In one letter on May 5th, 1970, Farrow writes and asks Wilder what his thoughts are on the George Bernard Shaw play Arms and the Man, for she had been asked to star in a production of it for television. She goes on to ask him his opinions on Uncle Vanya, The Glass Menagerie, Three Sisters, and The Seagull. “What do you think?” she writes to him, and received a quick response on May 19th with Thornton’s answers to every question. To answer her question about whether or not he likes the Shaw play, Thornton playfully says that he “won’t always tell the truth to Mia. It makes me uncomfortable,” but goes on to talk more deeply about the female role in the play. “As far as you go,” he writes, “I don’t think Raina is an interesting girl. Nor does Shaw (he’s interested in Serge and Bluntschli); he throws her to the audience for laughs and she is exposed as merely silly.” As a playwright, Wilder is able to provide insight into Shaw’s own investment in the characters of his play; Wilder does not let Shaw get away with failing to write a dynamic female character in this work, and therefore, warns Farrow against accepting the role. He elaborates on Shaw’s unequal attention to the male and female characters in the play, and tells Farrow that the female role is not deserving of her talent and creativity.

Although he inserts that he does not play the game bridge, he claims that he does have some knowledge of “the jargon of the game: Mia Farrow should play from the strong cards in her hand; she should play girls of conviction, of strength, and of intelligence. Her comedy must always be the comedy of a bright mind at work. That’s not Raina.” Wilder’s advice to Farrow is well considered and thoughtful as he insists that the roles she accept be as serious and complex as she is an actress. His attention to the nature of comedy is also noteworthy: Farrow, he writes, should engage in comedic roles that are not exclusively meant to be laughed at, but rather, comedic roles that explicitly express intelligence and cunning.

Thornton also wrote to Mia regarding his own artistic vulnerability in writing his last novel Theophilus North, which was published in 1973 and was later adapted into the film Mr. North in 1988. Wilder sweetly asks Farrow to keep him and his creative process in her thoughts, as he writes in 1972, “Please have a concern for me. As my book – I have been working very hard – approaches its end more and more earnest notes about suffering in life insist on coming to the surface – and I want to ‘get them right’ and then the book will end in a blaze of fun and glamour and happy marriages (at the annual ‘Servants’ Ball at Newport!); and you know what author I am trying to emulate.” Here, we see Thornton expressing his artistic anxieties about successfully writing about those pesky, insistent “earnest notes about suffering in life,” and he turns to Mia to voice those concerns. In a letter seven months later, Farrow writes, “Today I finished your book. It’s wonderful. I’m trying to decide what’s my favorite chapter – I can’t decide. I loved every minute of it and I’m awfully sorry that it’s over.” Their relationship is an unexpected mentorship and celebration of each other’s individual creative feats.

In addition to the constant stream of creative advice and mentorship, we get glimpses into Mia’s personal life as then wife to conductor and composer André Previn and devoted mother of eventually 14 children, 10 of whom were adopted. In an undated letter to Wilder, Farrow writes, “I read a wonderful new play by Tom Stoppard called Travesties.” I was asked to be in it but chose to nurse Fletcher instead.” These small moments where the professional and glamorous world of theater and film intersects with her intimate life as a mother provide insights into how Farrow considered the different arenas of her life and the choices she had to make to balance them.

Ruth Gordon makes another guest appearance in their correspondence when Wilder writes to Mia on May 17, 1973 after she tells him the good news that she had just been cast as Daisy in The Great Gatsby. “Ruthie tells me that The Great Gatsby is to be so big and important a production that we dare not hope to catch a glimpse of Mia.” And later, on March 17, 1974, he wrote, “Mia’s picture today is everywhere; never has a film had such advance publicity – not even Gone with the Wind – all of it wonderfully attractive.” There is a charming and whimsical nature to Wilder’s commentary on Farrow’s immense fame: an intimate recognition of Mia as a real person versus her role as a Hollywood starlet. Wilder and Farrow never failed to take the opportunity to celebrate each other in their individual creative pursuits, and their correspondence reveals an unexpected relationship between two artists of different mediums at vastly different times in their careers and lives.

Letter and playbill from the Thornton Wilder Papers YCAL MSS 108; Wilder’s letters to Farrow are in the Thornton Wilder Collection YCAL MSS 162