Students and scholars often wonder about how literary archives take shape, how they come to have their particular gaps and depths, how we might understand their organization and structure.

A range of factors may determine what happens to a writer’s papers both during and after their lifetime. As collections change hands – from a writer to her descendants, for instance – they can be changed in visible and invisible ways. If an archive becomes part of a research library collection, necessary institutional procedures – describing, organizing, rehousing, and conserving – may change it in still other ways.

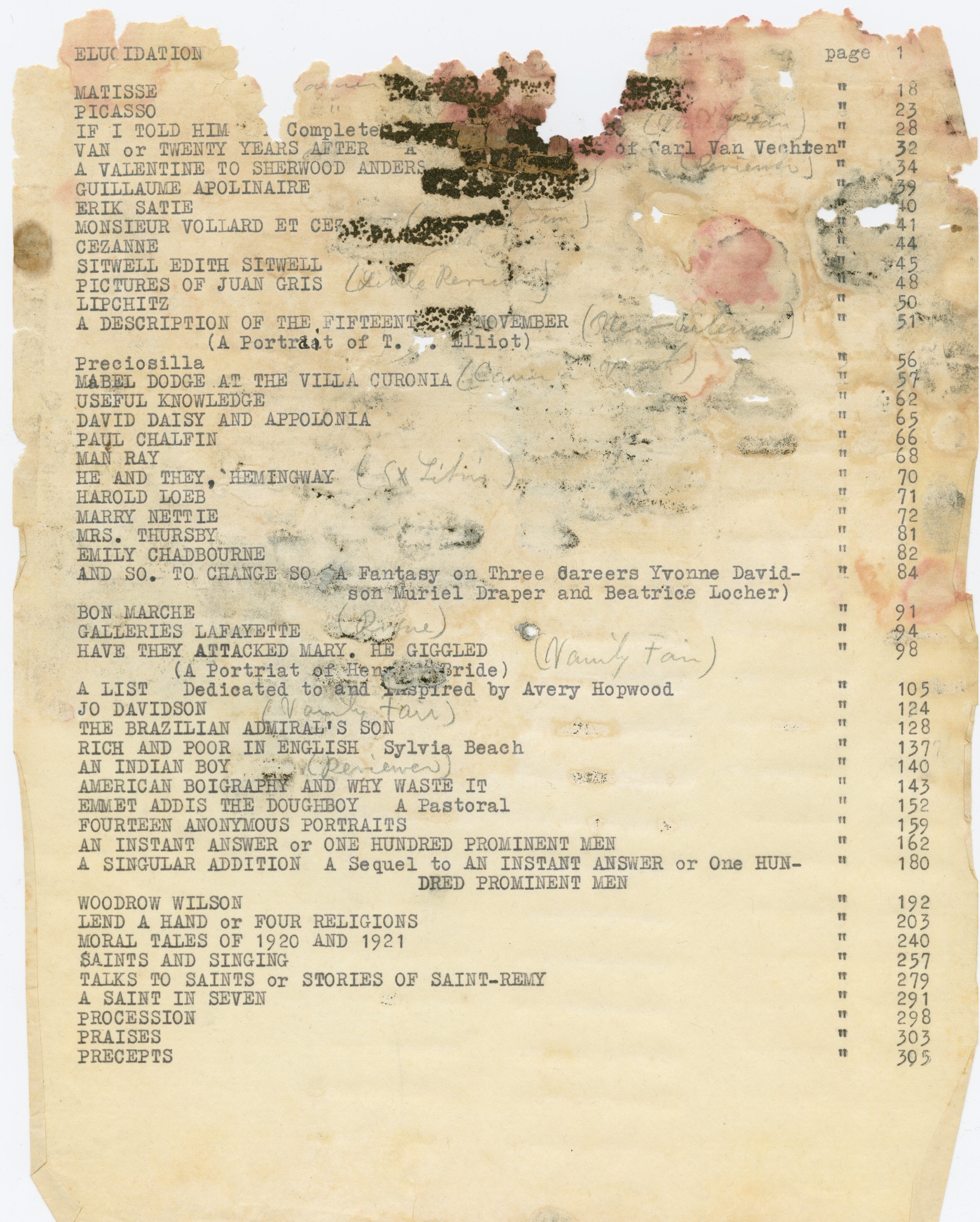

It can be tempting to think of an archive as an extension of a writer’s body of work, as work of art in a different form but intentionally guided by the creator’s aesthetic vision. And while is may be true that reading in archives can sometimes feel like reading a poem or viewing a sculptural assemblage, such metaphors can be misleading. Unless a writer makes their deliberate construction of an archive explicit (as is the case with the Simon Cutts Constructed Archive) their intentions and / or the context of the archive’s assembly may be lost. Sometimes, such information can only be known though painstaking research (Logan Esdale’s work on Gertrude Stein’s novel Ida and its relationship to the assembly of her papers offers an excellent example of this).

Nevertheless, the shape of a writer’s papers is very often determined (purposefully or accidentally) by the writer; in many cases, a writer’s archive is made up of what she chooses to or is able to save. Some writers save all their notes, their drafts, clippings, all their letters, and so on (the Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas Papers and the Langston Hughes Papers offer good examples of writers who keep A LOT of materials documenting their lives and creative processes). Others lose writings to fire, flood, or other calamity (Ralph Ellison’s loss of drafts of second novel, Juneteenth, in a house fire is one famous example). And some writers save little, lose track of papers, or live in ways that makes assembling an archive challenging (the Early Manuscripts and Papers of James Baldwin collection is an example of papers a writer inadvertently lost; the Delmore Schwartz Papers is an example of an archive assembled from the chaotic aftermath of a poet’s death; these are useful—if somewhat unusual—examples).

In some cases, descendants may physically alter or censor materials (as Ettie Stettheimer did her sister Florine’s diaries: Florine and Ettie Stettheimer Papers). Or the significance and value of a writer’s papers may not be known to descendants or others charged with managing a deceased writer’s personal effects. Zora Neale Hurston’s literary papers, nearly lost to a trash fire, are an important example that suggests the potential precarity of the literary records of even the most celebrated people of color and women (see: Looking for Zora Neale Hurston in the Archive by Melissa Barton).

It may be as impossible to know exactly how an archive is incomplete – things may be casually lost or purposefully destroyed; in either case absences in a writer’s papers may become invisible gaps. Sometimes absences become sources of scholarly speculation, questioning, and imagination. Even large and seemingly “complete” archival collections may leave scholars with questions. For instance, there are some 600 boxes of writings, correspondence, personal papers, and more in the Langston Hughes Papers and still scholars are frustrated that the collection includes little that concretely documents Hughes’s sexuality and romantic relationships (general readers, too, are interested what one journalist has called “The Great ‘Was Langston Gay?’ Debate”).

In libraries, where an archive can be understood in the context of other, related collections, gaps may become accentuated – as the lack of correspondence in the Mina Loy Papers becomes more conspicuous when her side of substantive correspondences can be found in the archives of friends, including the Carl Van Vechten Papers. The Loy Papers are, of course, enriched by such archival connections. Related groups of archives are quite common in the Yale Collection of American Literature and James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection and elsewhere at the Beinecke Library. The papers of friends, editors, and other writers serve to expand our view of many whose papers our in our holdings. Beginning from a collection mentioned above, for instance, researchers in the Carl Van Vechten Papers will find corresponding collections in the Hughes Papers, Stein Papers, and Luhan Papers and those of James Weldon and Grace Nail Johnson, Hutchins Hapgood, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Dorothy Peterson (to name only a few relevant collections).

The history of individual collections – if known – is typically recorded in the “front matter” of collection guides located in the Archives at Yale database. Other aspects of the Beinecke Library’s standard procedures for processing archival collections are well documented and publicly accessible (See: Archival Processing Manual for the Manuscript Unit of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library). Professional archivists preserve author’s intentions where that can be identified and documents’ original arrangement where possible (the Ron Padgett Papers, for instance, retain the poet’s organization of documents, including the location of their storage in his homes); they also work to arrange materials in sensible ways that allow scholars to understand what might otherwise be chaotic and unmanageable. Researchers are cautioned against assuming the physical arrangement or description of a literary archive in a research library necessarily reflects the archive creator’s own filing or storage of papers.

Many related questions – including what actually constitutes an “archive – are subjects of discussion among those involved in archival studies across multiple disciplines. Such conversations regularly consider, among other topics, questions about: the work of professional archivists and how it relates to the scholarly work of researchers; the concept of “discovery” in archival research; and the roles special collections in academic libraries might play in shaping archival study. Interested readers may find the following articles useful: “Please Stop Calling Things Archives” by B. M Waston (American Historical Association: Perspectives on History); “’The Archive’ is Not An Archives: Acknowledging the Intellectual Contributions of Archival Studies” by Michelle Caswell (Reconstruction: Studies in Contemporary Culture).

Pictured: Typescript draft of a Table of Contents from the Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas Papers.