During a recent visit from a class studying Reformation Europe, I brought out one of my favorite items in the Beinecke’s collection: a sixteenth-century prayer book that Sir Thomas More had with him while he was imprisoned in the Tower of London before his execution in 1535.

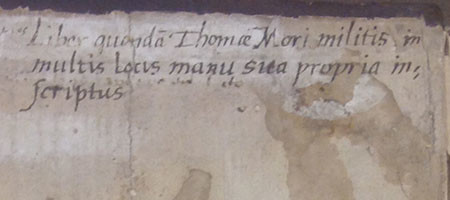

The volume, in a contemporary clasped binding, looks modest enough from the outside. In fact the book is two works bound together as one, a psalter and a book of hours, both printed in Paris in the early 1500s. When I opened the book to its inside front cover, the students were amazed to see an ownership inscription in More’s own hand.

More writes in Latin: “Liber quonda Thomae Mori militis in multus locus manu sua propria in scriptus.” Or: “Book of Thomas More, knight, annotated in various places in my own hand.”

The Latin inscription – many annotations in various places – piques the interest of even the most non-bookish and non-spiritual observers, who inevitably want to see what Thomas More had to say during his last days.

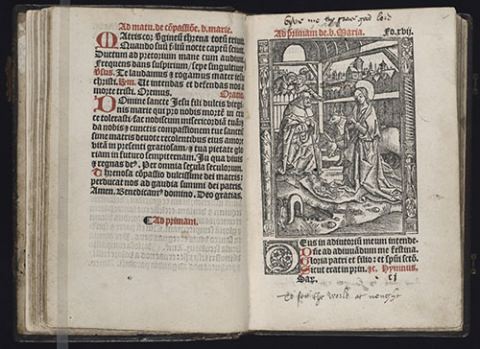

What a treat it was for the students to see that in the margins of the book of hours, following precisely the passion of Christ that is depicted in a series of woodblock prints, More has inscribed in early-modern English (not Latin, as one might expect) an exquisite set of verses meditating on his impending martyrdom.

Each of the forty-one lines of manuscript is poetic and moving in its own way, and a few are excerpted below:

Give me thy grace, good Lord,

to set the world at nought;

To set my mind fast upon thee,

and not to hang upon the blast of men’s mouths;

To be content to be solitary;

Not to long for worldly company;

Little and little utterly to cast off the world,

And rid my mind of all the business thereof;

Gladly to be thinking of God;

Many know the story of Henry VIII’s break with the Church of Rome so that he could divorce his queen, Katharine of Aragon. The 1534 Act of Supremacy declared Henry VIII head of the Church of England. More could not bring himself to sign the oath of allegiance to the Act of Supremacy, though he never spoke publicly against the king’s split with Rome or his marriage to Anne Boleyn. He preferred to remain silent on the subject.

Nevertheless, More’s refusal was interpreted by Parliament as an attempt to spread sedition, and he was imprisoned in the Tower of London. More held fast to his convictions despite Cromwell’s efforts to persuade him to sign the oath. As part of that persuasion, Cromwell ordered that More’s books and papers be removed from his cell in the Tower. Perhaps this prayer book remained.

More was tried and found guilty of violating the Treason Act and was sentenced to be drawn through London on a hurdle and then hanged until half dead. After that ordeal, he was to be castrated and disemboweled, quartered and beheaded, and his parts were to be set up on the gates of London, with his head upon London Bridge. Henry VIII commuted that sentence to mere beheading, and Sir Thomas More was executed on Tower Hill on July 6, 1535. His parboiled head was displayed upon a spike.

Four hundred years later, in 1935, More was canonized by Pope Pius XI.

Read a Yale University Library Gazette article about the prayer book here