Some highlights from the Jonathan Edwards Collection are on public display on the Beinecke Library mezzanine, September 30 through October 8, 2019, in conjunction with Yale & the International Jonathan Edwards Conference on campus. The materials on display were chosen by Kenneth P. Minkema, executive editor and director of the Works of Jonathan Edwards and Jonathan Edwards Center.

Learn more about the Edwards Collection at the Beinecke Library here

Learn more about the Yale & the International Jonathan Edwards Conference here

The materials on display include the following, with descriptions by Minkema:

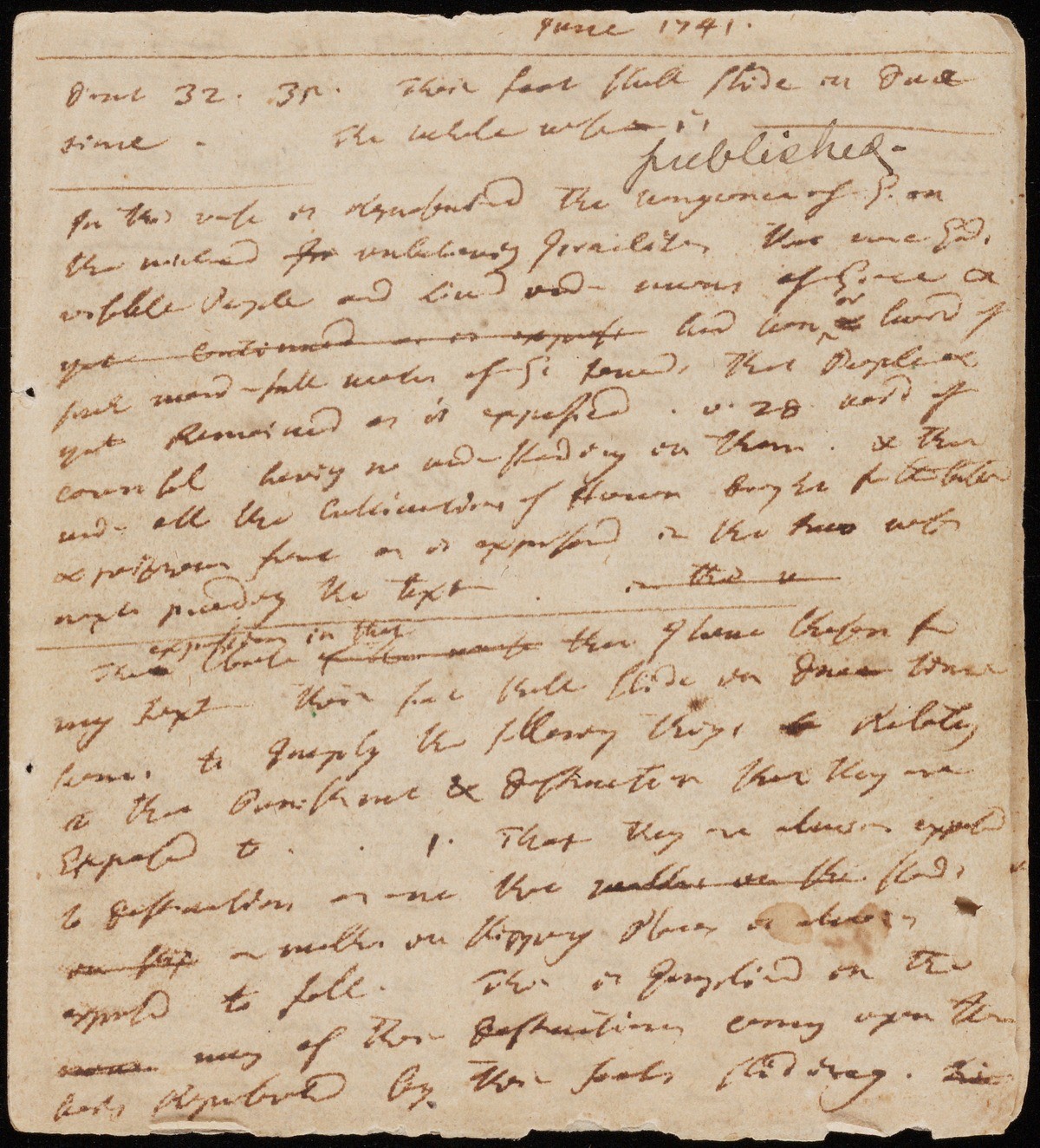

Sermon on Deuteronomy 32:35(c), 1741 (Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God)

Arguably the most famous sermon in American history, Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God, which Edwards originally preached to his church of Northampton, Massachusetts, in June 1741, before he re-worked it and delivered it at Enfield on July 8 of that year, in the midst of a transatlantic revival known as The Great Awakening. An eyewitness wrote that “before the Sermon was done, there was a great moaning and crying out throughout the whole House, What shall I do to be Saved? Oh I am going to Hell! Oh what shall I do for a Christ?” The sermon was printed in Boston, and Edwards repreached the sermon several times. Today, the composition is regarded as the epitome of the “awakening” or “hellfire and brimstone” sermon. (GEN MSS 151, Box 1)

“Miscellaneous Observations on the Holy Scriptures” (Blank Bible)

Edwards’ main repository of commentary on the Bible, the “Blank Bible” came to him from his brother-in-law, Benjamin Pierpont, around 1730. The volume is made of a disbound octavo copy of the King James Bible (1652) interleaved with quarto-sized pieces of foolscap, ruled to simulate the two-column format of the printed Bible for ease of locating glosses on particular verses, and then bound together. An efficient tool for the exegete, this source also became Edwards’ main index for his entire manuscript corpus. (GEN MSS, Box 17)

The “Miscellanies,” Book One

The “Miscellanies” is Edwards’ central series of theological and philosophical reflections, contained in nine volumes and totaling over fourteen entries. This sample page from Book One contains entry nos. 583-585, composed sometime in or around 1732. The titles of the entries on this one page–“Christian Religion, Mysteries,” “Christian Religion, Christ’s Miracles,” and “Heaven’s Happiness”–show the unsystematic, though not unconnected, nature of Edwards’ pursuits. For this reason, he numbered his entries and compiled an index to aid him in locating entries on particular topics. (GEN MSS, Box 18)

Draft on Slavery and the Slave Trade, 1741

The first and only time known where Edwards, a slaveowner himself, drew up his thoughts on slavery and the slave trade. He came to the defense of a fellow minister who was being criticized for possessing a slave. While defending a biblical basis for slavery, and labeling as hypocrites those who condemned others for slaveholding while still benefiting from the institution, Edwards did come out against the continuance of the slave trade, that is, forcibly taking persons from Africa and “disfranchising” them, or depriving them of their rights. This step, as well as Edwards’ ethical thought, would influence his disciples, the New Divinity, to advocate the immediate abolition of slavery and the slave trade. This item is in the Andover Newton Theological School Collection of Jonathan Edwards that came to Yale University as a result of the affiliation between Yale Divinity School and Andover Newton Theological School in 2017 (GEN MSS 1542, Box 1)

Medical Receipt from Sermon on Luke 12:35-36, 1742

Recycled by Jonathan Edwards for a sermon in December 1742, this is a prescription for Sarah Pierpont Edwards from Northampton’s physician, Samuel Mather, to treat a “hysterical original,” a uterine disorder, possibly following a miscarriage. In pre-modern medical diagnosis, hysteria was defined as a morbidly excited condition caused by a disturbance of the nervous system due to a disruption in uteral functions. The Edwards Collection has a number of such “receipts,” providing some insights into the treatment of diseases in the eighteenth century. (GEN MSS 151, Box 8)

Native Writing Exercise from Sermon on Ps. 27:4, 1756

In 1751, Edwards became the pastor and missionary at Stockbridge, Massachusetts, ministering both to English and to Mahicans and Mohawks. As part of his duties, he ran schools for Native boys and girls to teach them to read and write in English; indeed, one of the reasons the Natives agreed to live at Stockbridge was to become empowered through literacy as a means of protecting their lands through legal actions and acting as intermediaries between colonists and Natives in the interior. As a teacher, Edwards would assign Natives to complete writing exercises. Here is one such exercise, executed and signed by Ebenezer Maunnauseet, one of Edwards’ translators. The saying he transcribed over and over reads: “He who lives upon hope may die of disappointment.” (GEN MSS 151, Box 13)

Hannah Edwards Wetmore, Diary, 1736-1739

Hannah Edwards (1713-1773) was one of the ten daughters born to Timothy and Esther Stoddard Edwards of East Windsor, Connecticut, their only son being Jonathan. She married Judge Seth Wetmore of Middletown. She left behind a collection of private writings, such as a diary, miscellaneous reflections, excerpts from her reading, and letters – a valuable assortment, given the paucity of manuscripts by colonial American women. Upon her death, Hannah Edwards Wetmore’s writings passed to their daughter, Lucy Wetmore Whittelsey, who copied large portions of the archive out of devotion to the memory of her mother. The portion of the diary presented here is in her daughter’s hand. (GEN MSS 151, Box 24)

Sermon on Malachi 1:8, on fan paper, 1750

In constructing his manuscript sermons and notebooks, Edwards usually used foolscap that he cut up himself and assembled into booklets. Beginning in the mid-1740s, he increasingly incorporated another sort of paper into his manuscripts, much like rice paper in its thinness. For the source of this paper, we have to look to Edwards’ wife, Sarah Pierpont Edwards, and some of their daughters, who made fans, an essential item for any woman of the gentry class. The Edwards women decorated pieces of the paper with landscape scenes, done in ink and then painted. Next, they would cut the paper to shape, so that it fit on the mounts. This cottage industry left the unused remnants of the paper–including some bits of ink drawing and water coloring at the edges, as seen in this sermon manuscript–which Edwards would collect and repurpose. In this manner, an aspect of feminine production and expression found its way materially into the masculine domain of the sermon. (GEN MSS 151, Box 6)