With colleagues throughout the Yale University Library, and across the university, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library staff have been working to assist Yale faculty and students in the extraordinary efforts to transition rapidly to online teaching and learning for academic continuity through the remainder of the spring semester.

Every subject area or field of study has its own particular issues to address in order to optimize online learning. Teaching with special collections – normally a very hands-on and on-site endeavor – poses its own particular challenges and opportunities in the pivot to digital-only instruction in the present moment of public health challenge.

The 2020 spring semester has five Beinecke Library intensive courses – those with all or most of their sessions planned to be held in the classrooms in the library’s building at 121 Wall Street. There are scores of other classes that had scheduled one or a few sessions to engage with primary source materials in person.

Such courses are a distinctive part of teaching and learning at Yale. As the university’s 2019 Self-Study Report to the New England Commission of Higher Education noted, “When it comes to collections — from the university library to the galleries and museums —Yale stands alone among global research universities. More than 1,000 class sessions every academic year are taught inside our museums and libraries, with primary sources and art collections in hand. These advantages make a Yale education qualitatively different from any other.” The Beinecke Library itself hosts more than 500 class sessions in a typical year.

The following offers some insights from the first two weeks of the effort to take courses using library special collections “out of the archives, onto Zoom.”

African American Literature in the Archives

Beinecke Library’s Melissa Barton ‘02, curator of prose and drama in the Yale Collection of American Literature (YCAL), has taught AFAM 212/ENGL 221, “African American Literature in the Archives,” for a number of years. She has developed a well-honed syllabus that she brought to this semester’s edition of the intensive seminar, described as: an “Examination of African American literary texts within their archival context; how texts were planned, composed, revised, and received in their time. Students pair texts with archival materials from Beinecke Library, including manuscripts, correspondence, photographs, and ephemera. Readings include Lorraine Hansberry, Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, Zora Neale Hurston, and Richard Wright.”

Barton and her students were following the syllabus as planned – until the pandemic came and courses had to move online. She took the opportunity of the brief period before classes resumed to rethink, refocus, and retool the syllabus in light of the new reality for the final five weeks of teaching and learning,

Making the most of the moment, Barton determined to take up some new content: the joys and sorrows of archival digitization. “The students are working with digitized material for the rest of the semester,” she noted, so she decided the course would examine more closely the practice of digitization, with discussion about its pros and cons. The assigned readings for the April 1 class, for example, included discussions of Makiba J. Foster’s “Navigating Library Collections, Black Culture, and Current Events,” (Library Trends, Summer 2018) and Jenny Newell’s “Old Objects, New Media: Historical Collections, Digitization and Affect” (Journal of Material Culture, 2012).

Barton notes that it has been “a huge labor getting everything up and running” online in a short timeframe. She appreciates the “liveliness of the conversation” she and the 12 students have had to date on a Canvas discussion board. There’s one small, but notable change in the rules of engagement online that could never happen in the presence of collection materials: Barton’s revised syllabus tells students, “You are now permitted to eat and drink during class.”

She has also had to alter and adapt a key final assignment. Normally, students in the seminar plan hands-on, pop-up exhibits that are showcased in real time for each other and for Beinecke Library staff in 121 Wall Street. Students in past years have done their research and reviewed collections materials in the library’s reading room. They have then presented their final selections, with descriptive label text, in an open house setting, an opportunity to discuss their work with each other, with Barton, and with other library staff.

This year, the seminar is pivoting to a set of online-only web exhibits for the students to share with each other. While many thousands of digital images of the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of African American Arts and Letters can be found in the Beinecke Library’s overall digital library, far from all of the extensive collection items are digitized. In order to expand the universe of items students can use for their online pop-up exhibits, Barton has encouraged them to consult not only the Beinecke digital library but other digital collections in any relevant repository. The Umbra Search African American History database, for which Beinecke Library itself is a partner and contributor, is incredibly useful for this assignment.

Poetry and Objects

Karin Roffman ’04 Ph.D., senior lecturer of Humanities and associate director of Public Humanities at Yale, has taught AMST 346, “Poetry and Objects,” for several years, using the resources of both the Beinecke Library and the Yale University Art Gallery (YUAG). She describes it as a “course on 20th and 21st century poetry studies the non-symbolic use of familiar objects in poems.” In normal times, it meets alternating weeks in the Beinecke Library archives and the YUAG objects study classroom “to discover literary, material, and biographical histories of poems and objects.” Roffman collaborates closely with Beinecke Library’s Nancy Kuhl, curator of poetry in YCAL.

When it became clear early in spring break that courses might go online-only, Roffman spent as much time as possible in the Beinecke Library reading room, taking her own images of materials not already available in the digital library.

In their first meeting on Zoom on March 25, Roffman, Kuhl, and the students focused on poet Ron Padgett’s work and his literary archive at Beinecke Library. Students virtually viewed papers, photographs, and little magazines from the archive and considered these materials alongside some of Padgett’s poems (including early unpublished writing found among the poet’s papers).

Poetry and Objects students used their investigation of digital facsimiles of archival materials and printed books to prepare questions to raise directly with Padgett. The poet, originally scheduled to visit the class in the library on April 1, joined the class by Zoom instead that day. During the Zoom class meeting, the students showed Padgett specific documents and their prepared questions. Roffman helped to sharpen the conversation using the archival materials to provide a structure within which to consider the meaning of specific poems, the writing life, and Padgett’s own creative development over the course of his long career. Kuhl noted, “It was wonderful to see Ron interact with materials from his days as a high school student just beginning to write poetry.”

Like Barton’s seminar in African American literature, Roffman’s course assignments include a pop-up exhibition. Her students are also now working on independent online exhibitions in lieu of the planned program on-site, using resources from the collection and searching vigorously through the Beinecke digital library, Archives at Yale, and Orbis, and collaborating on Zoom to give one another feedback about their projects. Seminar students had spent their pre-spring break time in the library reading room hunting for objects for their exhibitions with great eagerness and curiosity and taking photographs, work that they continue to draw from for their online exhibitions.

Material Texts

Kathryn James, curator of early modern books and manuscripts, works closely with Peter Stallybrass, visiting professor in English, on ENGL 588, “Material Texts,” his course focusing on the material culture of reading, writing, and printing from 1400 to 1900 in England and America. Students in the class do hands-on research, drawing on the extraordinary collections of manuscripts and printed texts in the Beinecke Library. The course offers students an opportunity to explore archives and develop publishable projects relevant to their future research.

Stallybrass has taken the “Material Texts” course to Zoom “with aplomb,” James said, “drawing on the Beinecke Library’s digital collections—and those of our companion institutions, particularly the University of Pennsylvania and Folger Shakespeare Library. It’s been an amazing thing to see the rare book community around the world at work in this moment, and I think makes visible to students that to research in a library like the Beinecke Library is to take part in a much larger and incredibly generous intellectual community.”

Jonathan Edwards and American Puritanism

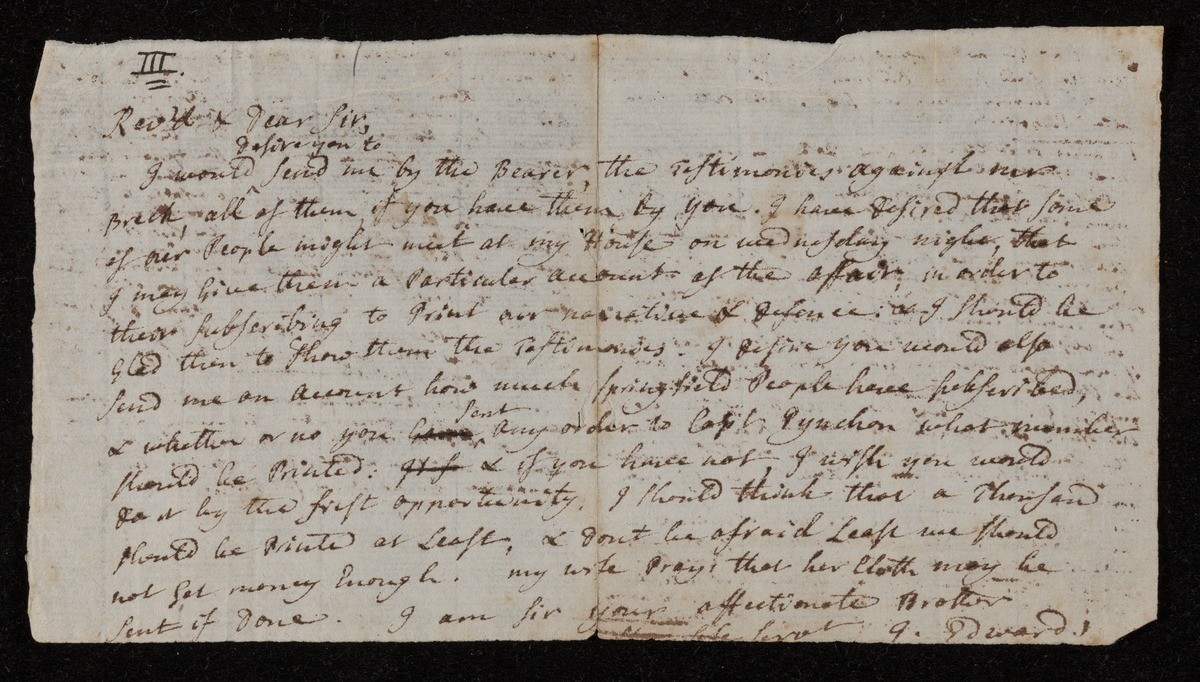

Kenneth Minkema, executive editor of The Works of Jonathan Edwards and of the Jonathan Edwards Center & Online Archive at Yale, also research faculty member at Yale Divinity School, teaches REL 738/RLST 739, “Jonathan Edwards and American Puritanism,” in the Beinecke Library, drawing on the iconic, extensive Edwards collection. He frames the course as “an opportunity for intensive reading in and reflections upon the significance of early America’s premier philosophical theologian through an examination of the writings of the Puritans, through engagement with Edwards’s own writings, and through selected recent studies of Euro-Indian contact.”

Minkema says, “This semester’s class on Jonathan Edwards at the Beinecke has given students the opportunity to interact with a much broader range of manuscripts and artifacts from the early modern period, which help to contextualize Edwards and his world. Each class has been structured around a related selection of items, each of which bear interpretations. One thing that students have come to see is that the frugal Edwards recycled many different sorts of documents and incorporated them into his manuscript notebooks and sermons—texts within texts. Also, students have been struck by the bodily and material aspects of Edwards’ intellectual production, and by his aesthetic concerns in his role as literary artist and author.”

The pivot to online teaching of this course benefits from the vast amount of Edwards materials that have been digitized. There are, for example, more than 1,600 “parent” records returned from a simple search of “Jonathan Edwards” on the Beinecke digital library, and most of these have multiple images, often dozens and sometimes hundreds of images per record.

“Nearly all of the Edwards materials are already digitized, and most available on the Beinecke Library site, in the Jonathan Edwards Collection,” Minkema observes. The recently acquired collection from Andover Newton at Yale Divinity School was scanned along with the Beinecke Library collection, and is accessible to Minkema for teaching and will be made available more broadly online in the future.

“Yale, even more than before,” Minkema says, is “the place to come to conduct serious study of one of America’s most significant religious figures (and one of Yale’s most distinguished alums! Class of ’20—1720, that is).” An added resource – for teaching and for the public – is the digitized version of the 26-volume Works of Jonathan Edwards published by Yale University Press. This, along with transcripts and edited versions of many other texts, as well as other supporting resources, are available on the website of the Jonathan Edwards Center.

Minkema emphasized the essential value of the primary source materials: “Besides the broader exposure, the ‘deeper dive,’ students have told me of the sense of immediacy they feel in having the original documents before them; they have a feeling that they are ‘looking over Edwards’ shoulder’ as he writes. The presence of an array of documents leads to different, and more detailed discussions than in a usual seminar, which only enriches the learning experience.”

Advanced Latin Paleography

Barbara Shailor first came to Yale in 2001 to serve as director of the Beinecke Library. Now a senior research scholar and senior lecturer in the Department of Classics, Shailor has been leading the CLSS 402/MDVL 563 seminar, “Advanced Latin Paleography.” Raymond Clemens, curator of early books and manuscripts, collaborates closely with Shailor on the course, one which addresses the challenges of using hand-produced Latin manuscripts in research, with an emphasis on texts from the late Middle Ages. Shailor draws the manuscripts and fragments for the course largely from collections in the Beinecke Library.

Most, though not all, of the Latin manuscripts in the collections have been digitized, so students can access digital facsimiles of an array of necessary and relevant materials. Shailor noted some of what is lost in a digital-only environment: “no feel of the parchment or paper, no smell of the manuscript; size can be difficult to gauge: is it a small little pocket book (as in a book of hours) or a big heavy horse of collected sermons?”

Clemens, Shailor, and their fellow scholars in the field have long been engaged with the opportunities, and the challenges, of using digital facsimiles for teaching and learning, and the early books collections are among the most available – and consulted – of the Beinecke Library’s digitized materials. Clemens said that he has taken further notes during this new period of virtual instruction to share with curatorial colleagues and staff of the library’s digital studio in order to further enhance digitization in the service of teaching and learning.

Other courses taught with Beinecke Library resources

In addition to the five intensive courses described above, Beinecke Library staff members are working to support many other classes that had been scheduled to visit the library and to use primary source materials to work hands-on with materials. Each semester, there are scores of such classes that come to the library for one or a few such sessions.

On April 2, for example, Timothy Young, curator of modern books and manuscripts, joined with Pamela Hovland, senior critic in the School of Art, for her ART 012 class, “On Activism: The Visual Representation of Protest and Disruption.” Young had previously met with the class in a Beinecke Library classroom before spring break, on March 5, to show them various forms of zines and activist publications, beginning with an edition of Thomas Paine’s Common Senseand going through Raymond Pettibon’s Tripping Corpse.

The students did research in various archives in Yale libraries prior to the closing of campus and are now working on their final projects, which will be an edition of their own zines that reflect their research and interests. On Zoom, Young served as a critic as the students gave updates on their work, providing feedback on their content and design and suggesting other resources they can use online to add to their works-in-progress.

Early Modern Curator James, meanwhile, is jointly teaching a an upper-level undergraduate seminar, ENGL 264 /HIST 405, “The Real Thing: Forgery and the Authentic, 1500-1800,” with Maria Del Mar Galindo. The course had its two scheduled sessions in the Beinecke Library prior to spring break. Their course asks the questions, “What is a forgery? How do we decide what is authentic?” as it offers a collections-intensive analysis of the history of scholarly engagement with questions of forgery, authenticity, and textual evidence, drawing on early modern and contemporary forgeries, including those of works by Shakespeare and Galileo.

Galindo and James, in one recent exercise, had their students turn their forgery assignments into an in-class auction on Zoom, with students representing imagined buyers (including the Beinecke).

View the “auction catalogue” for the class exercise here

Taking stock and looking ahead

All of the Beinecke Library staff involved with this moment’s transition to online teaching have noted that they are reflecting critically on what might be gained, and what can be lost, during this time without on-site, hands-on instruction. While most of their focus necessarily is on making it through these challenging times, they are also reflecting on what the present may portend and for the future of special collections-based learning.

Their students are doing the same. Barton said her students have “some very sophisticated” and “really beautiful thinking” about the affective experience of looking at materials digitally as opposed to in person. “They are teaching me things, as always happens,” she said. One of her students shared in a class discussion, “when I’m doing research in online databases, with the benefits of keyword search and chronological lists, I’m more likely to begin with a thesis and pick and choose evidence that fits. When I’m working with physical documents, or wading through folders, I’m more likely to let my thesis be buffeted and shaped by what I find.”

Another of Barton’s students observed, “digital organization makes us less receptive to the ambiguity, tangential connections, and all other unexpected aspects of opening a folder blind. So much depends on what keywords the archivist has associated documents with, and the scope of research seems much more narrow.” Most of her students, she reported, “still prefer to look at things in person.”

Barton noted, “My students seem engaged – and they seem quite stressed.” She has been cheered by how they are “supporting and checking in on each other” in small group online discussions. Barton also expressed thanks to the Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning for all of its guidance and assistance to her and all those teaching at Yale as they adapt their practice in this time of pandemic.

Amidst the uncertainty of the present, some things seem clear for the future: adaptability will continue to be essential, as will supporting and checking in on each other.

Note: this article reflects some early observations about online teaching from the first two weeks of the semester after spring break. Look for future posts about online teaching, including more perspectives from students, in the weeks ahead.