Gwendolyn Brooks

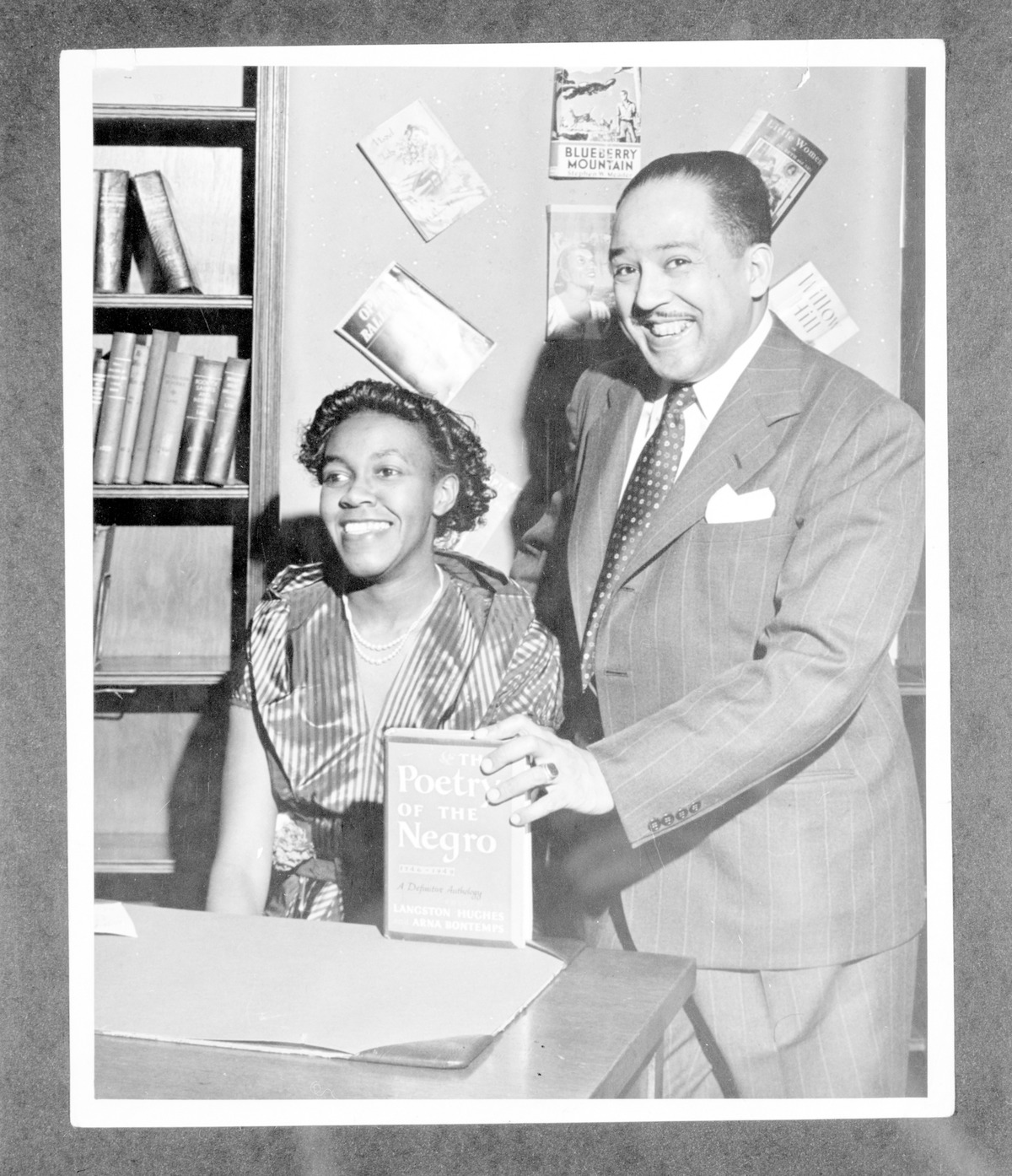

Last time, we found an addressed invitation to The Fear of Poetry Forum, a 1950 NYC event, from Muriel Rukeyser to Langston Hughes. Through letters, telegraphs, collaborations, and poems, we can draw a line from Hughes to our next American female poet, Gwendolyn Brooks.

Brooks and Hughes sent extensive correspondences to one another from 1942 - 1966 (JWJ MSS 26, Box 23). Below are some highlights from their exchanges:

“Lately I’ve been writing about the war, so that no one can say of me, SHE LIVED ALOOF FROM HER TIME!” — Brooks to Hughes on April 10, 1942

“Thanks so much for these poems. They’re spicy!” — Brooks to Hughes, August 7, 1945

“Your book is beautiful!….I love the wonderful humor, and the kitchenette dwellers portraits, and lots of things about it. More anon.” — Hughes to Brooks, September 17, 1953

“I am just about the only living Negro writer who still lives in the heart of Harlem.” — Hughes to Brooks, October 4, 1956

“Surely now I can die. Langston Hughes has dedicated a book to me.” — Brooks to Hughes, March 25, 1963

A letter from Brooks to Hughes in 1945:

“That they have seen fit to crown one of our youngest and most talented of poets with the laurels of a Pulitzer Prize is something that ought to make the dark-skinned astrologers of ancient times proud, if they see what’s going on from their resting places in eternity. Certainly this splendid award to Gwendolyn Brooks accents the current upsurge of the Negro in the cultural and artistic life of our America. With a little more Civil Rights and better schools and better wages, we could make even greater contributions to the cultural streams of our U.S.A. Do you hear me, Congress?” — “Pulitzer Prize to Gwendolyn Brooks Accents Upsurge of Negro in Arts” by Langston Hughes (JWJ MSS 26, Box 409, Folder 8530)

photograph of Langston Hughes with Gwendolyn Brooks

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917-2000) was an American poet, author, and teacher. She won the Pulitzer Prize for her poetry collection, Annie Allen, making her the first African American to win the Pulitzer. She was the poet laureate of Illinois from 1969-2000, the 29th Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, and the recipient of the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contributions to American Letters.

Researchers may be interested in the extraordinary poet if they wish to research black culture and literature in twentieth century America, black political movements and activism in the twentieth century, literary activism, poetry pedagogy, or visual culture. Researchers will also find fascinating words about motherhood, time, and friendship in the letters between Brooks and Langston Hughes.

As Lerone Bennett Jr. wrote, “[Brooks’s] poems celebrate the truth of her life. They celebrate the truth of blackness, which is also the truth of man. They reflect the wholeness of a person with deep roots in the soil of her people….In the fifties, she was writing poems about Emmett Till and Little Rock and the black boys and girls who came North looking for the Promised Land and found concrete deserts….Her poems are distinguished by a bittersweet lyricism and an overwhelming concreteness….one should give her words, all her words, their full weight.” (To Gwen with Love: An Anthology Dedicated to Gwendolyn Brooks)

Gwendolyn Brooks: Advice and Afterlives

Advice from Brooks

On the first page of the first publication of the magazine, The Black Position, edited by Gwendolyn Brooks and published by the Broadside Press in 1971 in Detroit, Michigan, Brooks wrote: “The Black Position will feature important black thinking on this time. The substance of the drama—”On this I Stand. Now. This is My Position.” / I promise to present the music and muscle of contemporary black pride as an excitement, a privilege, a responsibility.” (JWJ A B5672)

“Oh, little children, be good to John!— / Who lives so lone and alone. / Whose Mama must hurry to toil all day. / Whose Papa is dead and done. // Give him a berry, boys, when you may, / And, girls, some mint when you can. / And do not ask when his hunger will end, / Nor yet when it began.” — “John, Who is Poor” in Brooks’s poetry collection for children, Bronzeville Boys and Girls (JWJ Zan B791 956B)

“The understood black station now is an organic ‘Enough!’, a creative rebellion that often yearns toward revolution. There is certainly no going back to puny implorings, to integration-worship, to labeled slavery. Black literature: a reflection of the black mood, intuition, fury, and resolve. Where is it going?” — a capsule course in Black Poetry Writing, an advice book, 1975 (JWJ Zan B791 975C)

Brooks invited poets Keorapetse Kgositsile, Haki R. Madhubuti, and Dudley Randall to add sections to this book of advice for beginner poets. Brooks details the history of African American poetry and gives “A few hints toward the Making of Poetry”:

1. Language—ordinary speech. Today we do not say ‘Thou saintly skies of empyrean blue through which there soarest sweetest bird of love.’ Forget ectasy, ethereal, empyrean, wouldst, canst. Do not use ‘neath, e’er, ne’er, ‘mid, etc.

2. If you allude to a star, say precisely what that star means to you. If you feature a garden, speak of that garden most personally. If you have murdered in a garden, the grass and flowers (and weeds) will mean something different to you than to someone who has only planted or picked.

3. Try telling the reader a little less. He’ll, she’ll love you more, and will love your poem more, if you allow him to do a little digging. Not too much, but some.

4. Avoid cliches.

gentle flowers

sad lament

deepest passion

the wind howled

Occasionally a cliche can be redeemed:

the gentle flowers shrieked and killed the sun.

the sad lament was lovely, and I laughed.

For here the pictures and concepts are so outrageous that the cliche is elevated into a contribution

5. In a poem (and I believe in any piece of writing) every word must work. Every word, and indeed every comma, every semi-colon (if such are used—they needn’t be). Every dash (and poets should use few dashes: they are usually indeterminate, weak) has a job to do and must be about it. Not one word or piece of punctuation should be used which does not strengthen the poem.

6. Loosen your rhythm so that it sounds like human talk. Human talk is not exact, is not precise. Sometimes human talk ‘has flowers,’ but if it ‘has flowers,’ those flowers (as I have said in my poem ‘Young Africans’) ‘must come out to the road.’

7. You must make your reader believe that what you say could be true. Think of your efforts to be convincing and entertaining when you are gossiping. You use gesture, touch, tone-variation, facial expression. Try persuading your wordage—SOMEHOW!—to do all the things your body does when forwarding a piece of gossip.

8. Remember that ART is refining and evocative translation of the materials of the world!

“Loneliness means you want somebody. / Loneliness means / you have not planned to stand / somewhere with other people gone….But aloneness is delicious. / Sometimes aloneness is delicious.” — Brooks’s children’s book, Aloneness, 1971 (JWJ Zan B791 971A)

“I believe I’ll go right on writing about black people as people, and not ‘polemically,’ either.” — The Contemporary Writer: interviews with sixteen novelists and poets, 1972 (Za1 972 C769)

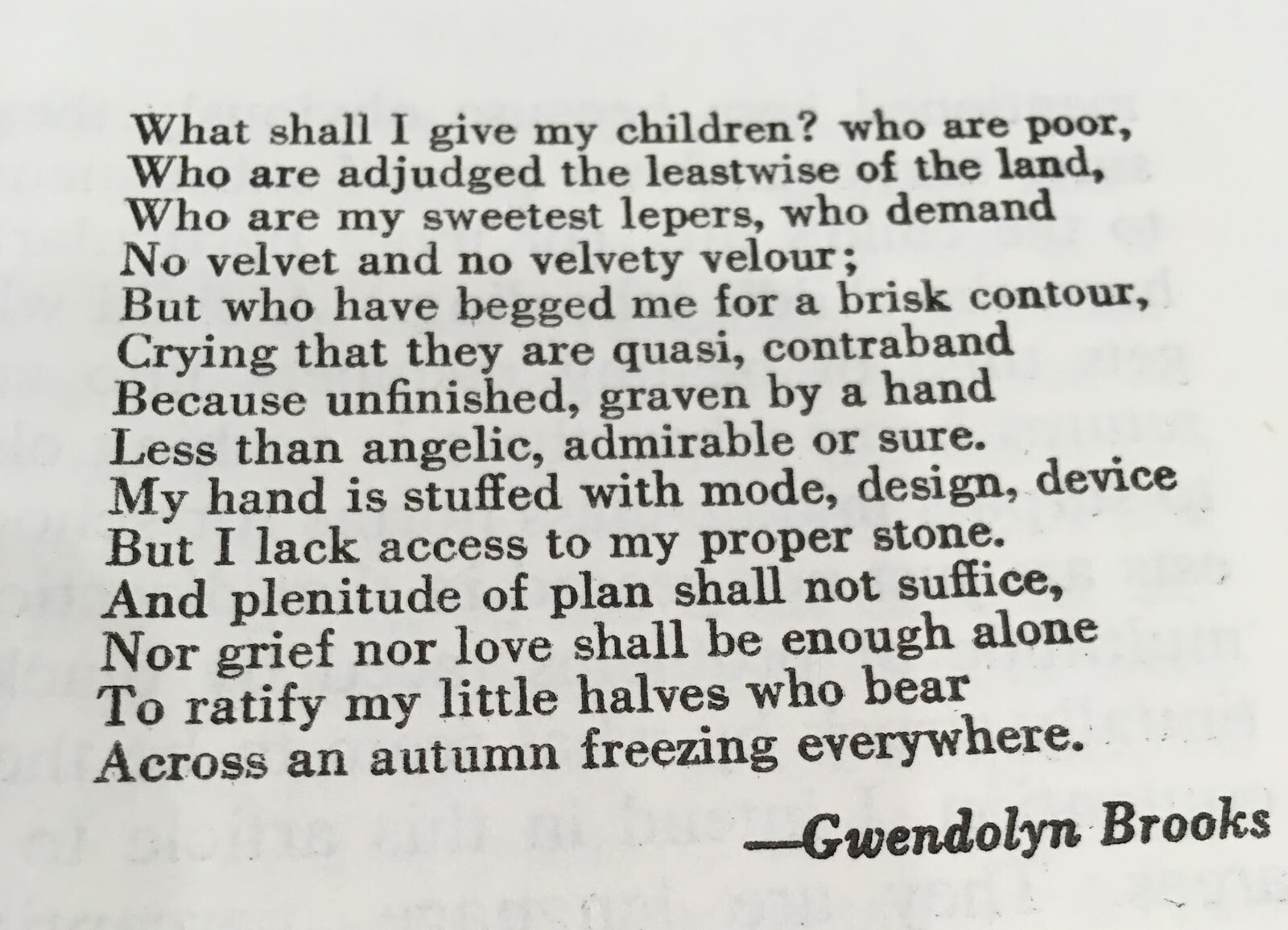

Words of advice from Annie Allen, 1949 (JWJ Zan B791 949A)

-

“You don’t have to go to bed, I remark, / With two dill pickles in the dark, / Nor prop what hardly calls you honey / And gives you only a little money.” (“Maxie Allen”)

-

“Watch for porches as you pass / And prim low fencing pinching in the grass.” (“the parents: people like our marriage / Maxie and Andrew”)

-

“To say yes is to die / A lot or a little. The dead wear capably their wry // Enameled emblems. They smell. / But that and that they do not altogether yell is all that we know well. // It is brave to be involved, / To be not fearful to be unresloved. // Her new wish was to smile / When answers took no airships, walked a while.” (“do not be afraid of no”)

-

“First fight. Then fiddle. Ply the slipping string / With feathery sorcery; muzzle the note / With hurting love; the music that they wrote / Bewitch, bewilder. Qualify to sing / Threadwise. Devise no salt, no hempen thing / For the dear instrument to bear. Devote / The bow to silks and honey. Be remote / A while from malice and from murdering. / But first to arms, to armor. Carry hate / In front of you and harmony behind. / Be deaf to music and to beauty blind. / Win war. Rise bloody, maybe not too late / For having first to civilize a space / Wherein to play your violin with grace.” (Part 4 of “the children of the poor”)

-

“Stand off, daughter of the dusk, / And do not wince when the bronzy lads / Hurry to cream-yellow shining. / It is plausible. The sun is a lode.” (Part 3 of “intermission”)

In her foreword to New Negro Poets: USA, published in 1964 and edited by Langston Hughes, Brooks quoted herself as saying in 1950: “Every Negro poet has ‘something to say.’ Simply because he is a Negro, he cannot escape having important things to say. His mere body, for that matter, is an eloquence. His quiet walk down the street is a speech to the people. Is a rebuke, is a plea, is a school. But no real artist is going to be content with offering raw materials.” (JWJ Zan B791 964H)

“We real cool. We / Left school. We / Lurk late. We / Strike straight. We / Sing sin. We / thin gin. We / Jazz June. We / Die soon.” — “We Real Cool” from 1960 edition of Brooks’s collection, The Bean Eaters (2010 Folio S46 I.14)

Words of advice from Very Young Poets, Brooks’s little, green, instructive book “to children who want to write poetry” and “dedicated to all the children in the world” (JWJ Zan B791 983V)

-

“Try different ways of saying a thing. Then choose the way that seems best.”

-

“Be yourself. Do not imitate other poets. You are as important as they are.”

-

“Sometimes it is hard to say exactly what you want to say. Do not give up. Keep trying. Sooner or later, you will think of the words that are right for your poem.”

“Books are meat and medicine / and flame and flight and flower, / steel, stitch, and cloud and clout, / and drumbeats on the air.” — 1969 bookmark with a Brooks poem (JWJ Zan B791 969B)

Amongst a collection of large broadsides, brightly illustrated and tied together in an ornamented folder, Brooks’s 1971 broadside includes the words: “The one hand is your Language. / The other hand is your Art.” and “Let / black love survive the Calculated Blaze. / Let / black love survive the Challenge and the Blood.” (JWJ ZZan1 C1)

In Brooks’s introduction to Johari Amini’s 1970 poetry collection, Let’s Go Some Where, she wrote: “Even the most exquisite freedom needs an anonymous spine of discipline” and “There is such freedom in what the ‘new’ black poets are doing now. They feel so FREE to do what they want to do, to commit Sins against any of the Academies, against any of the musty Musts.” Amini wrote a poem in honor of Brooks, entitled “For Gwendolyn Brooks — A Whole & Beautiful Spirit.” (JWJ Zan L356 970L)

Afterlives

Countless others also wrote poems, created anthologies, and held events dedicated to and in honor of Gwendolyn Brooks, both within her lifetime and afterwards.

“Members of the Black Chicago community decided during the summer of 1969 to ‘present roses to the living.’” In Lerone Bennett Jr.’s introduction to the anthology, he wrote: “we have a book which is an extraordinary gesture of love and perhaps the most unprecedented act of communal generosity in the cultural history of Afro-Americans.” — To Gwen With Love: An Anthology Dedicated to Gwendolyn Brooks, 1971 (JWJ Zan B791 N971T )

Each poem is this next collection is a Golden Shovel poem, a form created by National Book Award winner, Terrance Hayes, in which the last words of each line of the poem are words from a line or a whole line taken from a Brooks poem. — The Golden Shovel Anthology: New Poems Honoring Gwendolyn Brooks, 2017 (Za1 2017 G565)

The Chicago Collective: Poems For and Inspired By Gwendolyn Brooks by Stephen Caldwell Wright (JWJ Zan W939 990C)

Brooks was included in the 20th century poets postage stamps collection, alongside Bishop, Hayden, Stevens, Plath, and others: